Last summer, I read Maria Todorova’s Imagining the Balkans. Todorova’s monograph takes a critical eye to the concept of the Balkans in Western European imaginations. Buried in her enlightening work is a piece of advice for readers: to consult Laird Archer’s Balkan Journal. Archer was an American diplomat stationed in Albania and Greece in the late 1930s and early 40s. His account contains some fascinating snippets of daily life in the two countries just before and during Italian, and then German, occupation. Laird was closely connected to many Albanian government sources during the period, and when relating the resistance to Fascist entrenchment in Albania, he notes that a government in exile has been set up in Istanbul. It soon emerges that the city is pivotal for two reasons: it hosts those loyal to Albanian sovereignty; and Robert College, the famous American educational institution in the city, is also the alma mater of some of the collaborationist politicians in Tirana.

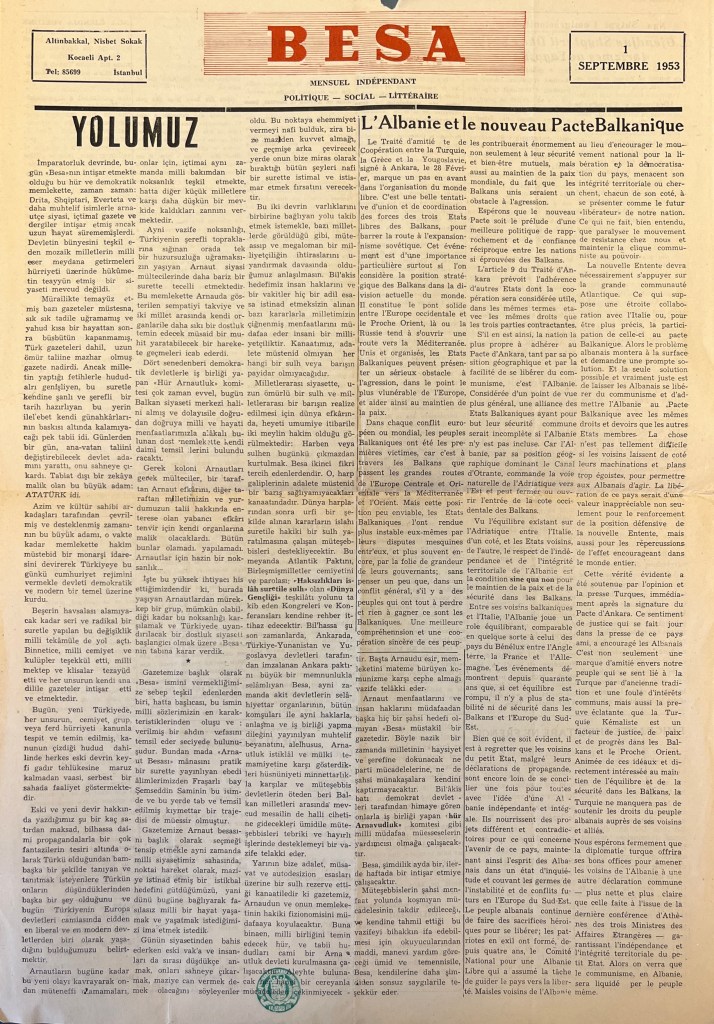

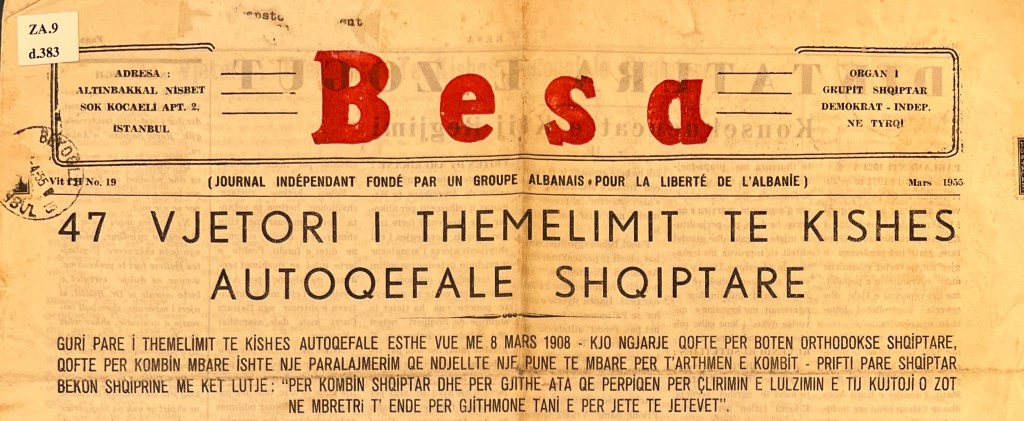

Unfortunately, the British Library doesn’t hold any printed materials from Albanian exiles in Istanbul from the turbulent 30s and 40s. But the afterlives of their struggles are attested in some its periodicals, most notably the newspaper Besa (ZA.9.d.383). The publication, which first appeared in 1953 (a year after the Türk-Arnavut Kardeşliği Derneği was formed), contained pieces primarily in Albanian, as well as French and Turkish. The former were undoubtedly intended for circulation among exiles, the diaspora, and, possibly clandestinely, Albanians in Albania itself. The latter group of pieces largely mimicked those in Albanian (although only a small number were published in either French or Turkish) and were likely meant to spread exiles’ views and opinions among Turks and the international community more widely. Besa also contained photographs and other illustrations in black and white, and published continuously until the mid-1970s, or possibly later.

Besa is interesting for a few reasons, even for those who don’t read Albanian. The first issue was produced as two separate editions: one Albanian and the other a Turkish/French combination. Thanks to the latter, I can tell you that this was an ambitious project, one that aimed to promote Albanian interests for both exiles and “colonies,” presumably the historic diaspora. It was founded by the Hür Arnavutluk (Free Albania) society, largely exiles, and proudly anti-Communist. The opening editorial makes it clear that Besa is also staunchly pro-Kemalist, with its contributors convinced that Turkey is one of the freest, most liberal members of the European community. These are the early Menderes years, the first few after the end of the one-party system in the country and the start of Turkey’s participation in NATO, so it’s easy to understand the democratic euphoria.

The editorial leadership of Besa was keen to ensure longevity and regularity for their paper – they say as much in the opening editorial. This was evidently illusory, as they failed to meet the monthly periodicity they’d planned for, let alone the weekly one they’d hoped to achieve at a later date. Publication wasn’t sporadic, but it also wasn’t regular. The British Library’s holdings are far from complete, which means that I can’t give issue-by-issue coverage of changes in language, size, or illustration. But by 1954, it’s clear that the two separate issues (Albanian and Turkish-French) had merged into one. After this, it appeared at irregular intervals. But there can’t have been serious threats to its existence, as the paper continued to include illustrations in the form of photographs, always black and white, which would not have been cheap to maintain.

What sort of stories did Besa carry? The content is not much different from many other exile publications. It’s a mixture of news from the homeland, sometimes brought out by defectors or refugees; news from the diaspora, including cultural and community events; plenty of opinion pieces about Albania and the policies of neighbouring states (especially Greece); highly positive reviews of events in Turkey; and no small order of historical writings about the early and recent history of the Albanian people and lands. Pretty much anything and everything, interrogated from the point of view of the Albanian struggle for democracy, was fair game.

The early issues of the newspaper list Dr. Ali Koprenska as the managing editor, but his name disappears from the masthead. It’s present elsewhere in the publication until 1965, and we then find Kazım Prodani awarded the title of managing editor until the end of the run. The editorial office address, meanwhile, remained on Nisbet Sokak (possibly Şişli?) up to 1956. The Library’s copies stop here for a while, and then pick up again in 1964, when the office has moved to Beyoğlu, where it remains until 1974. And, while some of the earlier issues have authors’ names attached to the articles, these largely disappear in the later issues, which either means that contributors declined to be associated with their writings, or that most of these writings were done by a small group of authors.

The title Besa is notable for a few reasons. It translates to Pledge of Honour, which is apt for an exile work. But Besa yahut Ahde Vefa is also the name of an Ottoman Turkish play penned by the intellectual Sami Frashëri or Şemseddin Sami. One of the most notable names in late Ottoman linguistic reform and Albanian nationalism, Sami came from a family of politically active scholars and activists. His play was intended to promote a positive view of Albanians in Ottoman society, but also spurred nationalistic honour and a yearning for self-determination among Ottoman Albanians. The founders of Besa make it clear in the opening editorial of the inaugural edition that both the Frashëri connection and the meaning of the word besa induced their decision to use it as a title.

Besa in its mid-20th century form is mentioned only as a one-line comment in Kudret Emiroğlu’s fairly comprehensive overview of Albanian-language journalism in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey (‘Osmanlı Dünyasından Cumhuriyete Arnavutça Süreli Yayınlar’). It’s part of a powerhouse edition of the journal Kebikeç, issue 50 (2020), which brings together dozens of scholars of the non-Turkish press in the Ottoman Empire and its successor state. Thanks to this article, we learn that the name was also used by Thoma Avrami for a number of Albanian-language publications in Cairo in the first few decades of the 20th century. In the same issue of Kebikeç, Isa Blumi tells us that Besa-Besën was the title of a contemporary publication produced in Cairo and of an Albanian cultural organization in Boston in his contribution, ‘Balkanlar Kültürel Elitinin Paradoksal Dağılışı: Bir Osmanlı Arnavut Hikayesi.’ Finally, the name also appeared in the title of a biweekly newspaper published in Istanbul starting in 1908, Bashqim Besa, which ran for a full 38 issues.

The National Library of Turkey indicates that Bashqim Besa was a short-run “local paper” from Istanbul published by Mehmet Fraşen in 1908-09. Emiroğlu says that issues in the Hakkı Tarık Us Collection also include Aleksi Tepedelen as one of the concessionaires (imtiyaz sahibi). The Library has made available three issues of the work on its digitized newspapers site, all of them in such low resolution that it’s pretty much impossible to read anything but the titles or mastheads. But what we can see if that the paper was bilingual Ottoman Turkish-Albanian, with two pages for each language. The Albanian text appears to be printed in the modified Latin script known as the Bashkimi script. The images are too low-res to determine whether they include the 1908 reforms supported by the Frashëri brothers. But what is clear, given the Wikipedia article about the history of the Albanian alphabet, is that this paper was likely not pro-CUP, as it promoted the use of Latin rather than Arabic script for the language. In this respect, it’s not a lone wolf on the late Ottoman periodical scene, as İsmail Eren’s “Yugoslavya Topraklarında Türkçe Basın”, originally published in Sesler in 1966, attests. I’ve only found the Serbo-Croatian translation online (published in 1968), where Eren lists Başkimi Kombit-İttihad-i Milli as a bilingual and biscriptual Albanian and Ottoman Turkish newspaper published in Bitola, now North Macedonia, in 1910.

Surely, our Besa hasn’t passed by totally unnoticed, has it? Sources in languages other than Turkish or Albanian are mighty hard, if not impossible, to come by. Albanian is outside the realm of my abilities, but even in Turkish there is scant material to commemorate this 20-year project. This is a real shame, since Besa wasn’t the only game in town. That same issue of Kebikeç I mentioned above contains another article, this time by Halil Özcan, about the contemporary irregular periodical Vardar Gazetesi (‘Sürgündeki Arnavutların Sesi: Vardar Gazetesi’). Özcan provides a fairly comprehensive overview of the history of the publication, which was under the editorship of Şemsettin Davutoğlu and connected to the Türk-Arnavut Kardeşliği Yardımlaşma Derneği. Founded in 1951, the Association was originally headed by the former Prime Minister of Albania during the Nazi occupation, Rexhep (Mitrovica) Bor. Özcan qualifies the organization as being composed of anti-Hoxha émigrés, without implying any connection to Anatolian Albanian communities. He stresses its initial linkages to the Turkish state and Albanian Muslim religious communities in Egypt. As time passed, the Association fell out of favour with the exile community, and its membership dwindled rapidly over the 1950s.

Vardar was stridently anti-Communist and nationalist, toeing a strongly pro-Turkish line that frequently clashed with Greek irridentism as well as Socialist Yugoslavia’s policies. Together with its celebration of Turco-Albanian friendship, these were meeting points in the visions of both Besa and Vardar. The latter newspaper also came out in support of Orthodox Albanians who were under considerable assimilatory pressure from the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, despite the existence of a separate and recognized Autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church. This was especially the case following the 6-7 September 1955 pogrom targeting Greek Christians, as well as other ethnic minorities, in Istanbul. But it’s clear that Vardar approached such issues from without the Orthodox community, arguing for supra-religious national unity for the sake of the Albanian nation. What isn’t clear is where the difference between Vardar and Besa lay. Was it an issue of religion? Or, more likely, given Besa’s prominent anti-Fascist line, were political divergences within the Albanian community the source of the split? It will take someone with a knowledge of Albanian to find and interrogate all issues of Besa to settle this for certain.

Besa might have disappeared from the streets of Istanbul in the 1970s, but its promise wasn’t forgotten. A new periodical of the same name was published from 1993 onwards as part of a renewed lobbying effort by Albanians in Turkey, largely around Kosovar rights. The question remains, however, what happened to Besa’s editors and contributors? Did they fall prey to the turbulence of the late 1970s and the repression following the 1980 coup? Did they lose support within the community? The collapse of the Communist regime in 1991, and the emergence of Kosovo as a central flashpoint in the 1980s and 90s, clearly shifted the dynamic of Turco-Albanian relations following the Cold War. But Besa remains as a tribute to a different type of interaction, and to an Istanbul that functioned as a clear base of operations in the struggle for a democratic Albania.

Leave a comment