CONTENT WARNING this article contains images of bare breasts and buttocks, as well as depictions of sex and sexuality!

To quote Salt N Peppa, Let’s talk about sex, ba-by!

After all, despite being a non-negligible part of our lives, we rarely talk about sex or sexuality when looking at library collections. It’s not like there aren’t plenty of books that deal with these topics, whether fiction or non-fiction. I’m quite keen on building up a collection of them (at least in Turkish and Kurdish), and I had the great opportunity to talk about some of the materials I’ve amassed in the Methods in Question Series at Cambridge University in early 2019. But I’ve acquired so, so many more similar publications since then that it would be a sin not to share at least some of them with you. One recent purchase, in particular, raised so many questions (and eyebrows, if only one could have many eyebrows), that I felt the burning need to delve deeper into its content, context, and history. So, in this blog post, I’m going to share a few thoughts about a flimsy-looking periodical under the title Eşim ve Ben (My Spouse and I). Don’t worry, it won’t all be book history and Turkish politics; there are plenty of salacious images along the way to keep you interested too.

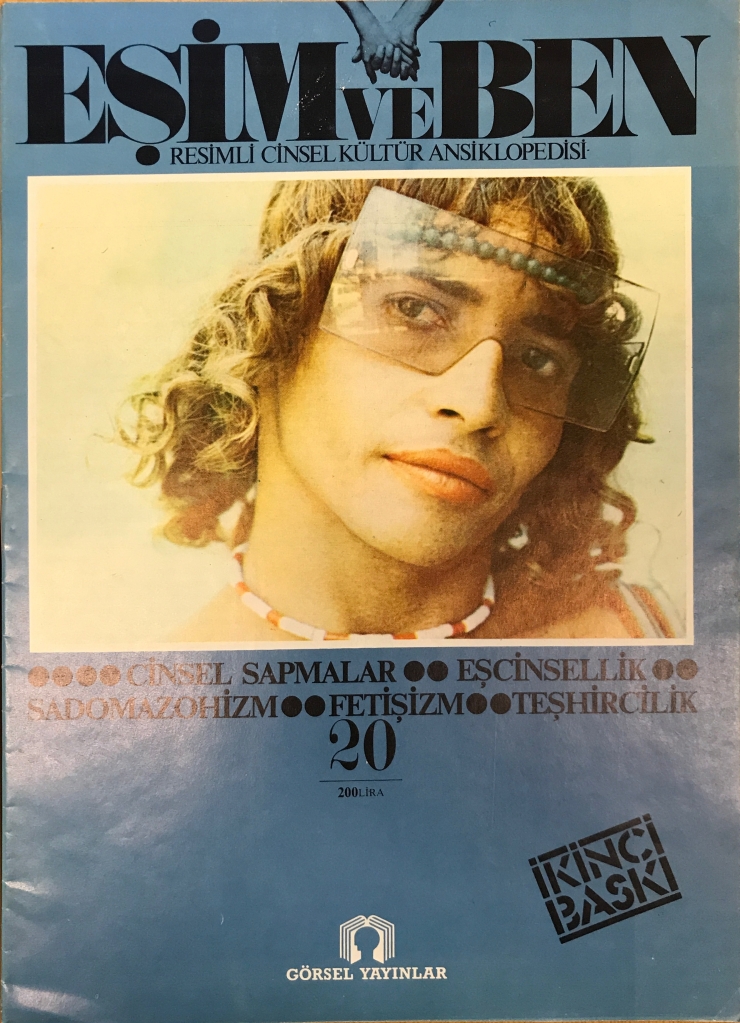

Eşim ve Ben is a 24-part series of soft-cover publications that were produced in 1982-83, although it appears that second and third prints were issued in 1984 and 1985, at least for a few of the issues. The title, which makes use of the gender-neutral word eş (same, equal, spouse), would indicate that these magazines were intended for spouses of all genders. This wouldn’t have been the case if the title had been, say, Karım ve Ben (My Wife and I) or Kocam ve Ben (My Husband and I), given that same-sex marriage was (and continues to be) unrecognized by the Turkish state. A quick perusal of the imagery employed, though, shows a bevy of bare-breasted, nubile white women in their early 20s or 30s; the sort of visual stimulation that is generally directed at heterosexual cis-men. But to treat Eşim ve Ben as nothing more than a bit of popular titillation for a patriarchal society would be a mistake. For all its flaws, the magazine is packed with fascinating information about sex, gender and sexuality at a crucial point in Turkey’s contemporary history.

Issue 2, devoted to women and men, what is love?, love and sexuality, and sex roles

Issue 7 on positions, group sex, masturbation, and the Kama Sutra

Issue 15 on the modern family, divorce, extramarital sex, and fornication/adultery (zina)

Eşim ve Ben was not the product of a well-known publishing house or famous editors. The publisher, Görsel Yayınlar, is associated with a few hundred items on the catalogue of the Milli Kütüphane. Most of them are translations of foreign literature, as well as a number of pictorial encyclopedias or studies of art, cinema, tourism, history or the body. Although the complete chronological range of publications spans from 1975 to as late as 1998, it’s clear that the firm’s heyday was between 1981 and 1992, when easily 90% of the titles associated with it were produced. The owner of Görsel Yayınlar, Ragıp Yazır, was in fact the editor of the first item published by the company, a pictorial encyclopedia of art history that appeared in 1975. He’s not tied to any other publications in the Milli Kütüphane’s database (but does appear against a few titles in WorldCat), which likely means that he was not responsible for the authorship or collation of many more items, although he clearly had a hand in the publication of a number of works. His name does show up in an oral history of Sirkeci from 2013, and, briefly, as the individual who helped Erdal Öz set up Can Yayınları in 1981.

The articles in Eşim ve Ben don’t carry the names of individual authors or translators. What we know of those who contributed to the encyclopedia comes from the list of individuals who fulfilled these roles at the start of each issue. Issue 19 provides us with the names of ten people under the title of “metin” or text. Of these, Suay Aksoy (perhaps the former head of ICOM?) appears in the Milli Kütüphane’s entry for the encyclopedia, and Ayşın Candan, Yaşar Çabuklu, Ayşe Erkmen (the famous artist?), and Nazım Güvenç are all listed as the authors of works appearing from the late 1980s onwards. Many of these are titles related to politics, economics and sociology with a particularly leftist bent. Osman Deniztekin and Orhan Koçak were both translators of a number of books and authors in their own right. Deniztekin regularly contributes to online publications in English, and Koçak even produced a Turkish version of some of Trotsky’s writings. Only Erdal Albayrak (not the Coach of the Turkish Football Federation), Refik İlhan, and Muzaffer Sönmez (the actor?) do not have any further entries in the Milli Kütüphane’s databases, indicating either that they continued with collective publications, possibly further behind the scenes than as authors or translators; or that they sought their fortunes in other industries.

Why, you might ask, would authors, editors and translators committed to a Marxist view of the world spend several years working on an encyclopedia of sex? The answer might lie in the socio-political context of the time. On 12 September 1980, a group of military officers led by Chief of the General Staff General Kenan Evren overthrew Turkey’s elected government. One of the country’s bloodiest coups, if not its bloodiest, the soldiers who toppled the government justified their actions based on the turbulence and political violence of the 1970s. During this decade, a series of governments of both the left and right rotated through power as clashes between supporters of leftist and far-right groups escalated (see also Dr. Sabri Sayarı’s “Political Violence in Turkey, 1976-80: A Retrospective Analysis”). General Evren’s regime argued it would put an end to this spiral through a crackdown on both groups. This involved harassment, arbitrary arrests, disappearances and extrajudicial executions. Although the junta claimed it was coming down on both sides equally, in practice the sword fell more often on those of a Marxist or Maoist persuasion than on residents of the right end of the political spectrum (sound familiar?). Back in 2015, I wrote about the economic impacts of the coup in this piece published in the SOAS Journal of Postgraduate Research. I won’t dwell on the coup and its political aftershocks at length here, but it suffices to say that 12 September had profound impacts on Turkish politics and society, many of which are still felt today. A much more comprehensive understanding of these can be discovered in the most recent edition of 40 Yıl 12 Eylül, edited by the prolific Tanıl Bora.

What is worth exploring here are the cultural impacts of the 1980 coup. Evren’s cadre of plotters used their three years in power to alter radically the composition of Turkish culture and society. While ostensibly seeking to depoliticize the public sphere, the military junta opted for a clearly conservative tact, one embodied in the right’s quasi-ideology of the Turkish-Islam Synthesis (Türk-İslam Sentezi). This aimed at marrying the country’s long-standing hard nationalist stream with a much more pronounced emphasis on Sunni Islam, arguing that the two were inextricably intertwined throughout history. An unintended consequence of the depoliticization process, however, was that intellectuals and public discourse were often pushed towards the personal, rather than the overtly political. In contrast to previous decades, the 1980s saw a veritable explosion of narratives and movements based much more on lived experience and identity than on ideology. In his piece “New Social Movements in Turkey Since 1980,” Sefa Şimşek has outlined this process in detail, with a particular view to topics such as religion, ethnicity, and the burgeoning feminist movement of the post-coup era. Dr. Yeşim Arat has honed in even more tightly on the role that feminists played in broadening civil society and creating a new public space tolerant of the sorts of exchanges necessary for a democracy independent of statist organization. A multiplicity of personal views was now the norm, even if that plurality of opinions was not always accepted by all actors within the arena of public discussion.

Issue 23 featuring cinema and sexuality, Hollywood, and sex in local and foreign cinemas

Issue 24 focusing on sex in local and foreign cinema, alongside an index and glossary of terminology

What was so important about this post-modernist boon within Turkish culture? For one, it showed that General Evren and his cronies had failed. After all, any second-wave feminist would have told them that the personal is political. The private thoughts, feelings and experiences expressed by those participating in this new trend all encapsulated ideas and realities of power dynamics, systemic racism and discrimination, body politics, and historical narratives that challenged and subverted the state’s official metanarrative of Turkish nationhood. Melis Umut, currently studying at Stony Brook University, unpacked such ideas within Turkish cinema from the 1980s in her Masters thesis, entitled “Representation of Masculinities in the Post-1960s Turkish Cinema.” The eighties didn’t quite represent a feminist reimagination of the motion picture industry, but they did reflect a change in sensibilities about women’s sexuality and its relationship to the entrenched patriarchy of both the right and the left. Often directed by men, these new movies imbued sexual beings with a humanity they had previously been denied, and brought the excitement, aspirations, hopes, hurts, and expectations of Turkish women into public discussion. In doing so, they also altered the way men’s sexuality was discussed, and the links established between sex, masculinity, vulnerability, and power.

Issue 21 focused on fashion, cosmetic surgery, advertising and eroticism

Issue 22 focused on sexuality in art, image and theatre, literature, music and pornography

This, finally, is where I think the leftist sensibilities of many of the contributors of Eşim ve Ben met their subject matter. Let’s be clear: the 1980s were far from a golden era in which Turks openly explored and expressed their sexualities without fear of repression or violence. In fact, as Dr. Cenk Özbay points out in his explanatory piece “Same-Sex Sexualities in Turkey,” these were the exact threats that homosexuals often faced throughout the decade. But it was also during this time, particularly towards the end of it, that open expressions of non-conformist sexualities became more widespread, and that same-sex relationships and desire appeared in popular cinema and literature. Perhaps this was partly assisted by the focus of the press on salacious and titillating stories, as Dr. Selçuk Ural and Dr. Yasin Ercilsin have explored in their co-authored paper, “1980-1983 Yılları Arasında Türkiye’de Basın ve Sanat Hayatı” (“The Press and Life of Art in Turkey Between 1980-1983”). Ural and Ercilsin explain that an emphasis on the “apolitical” in the early 80s pushed journalists, editors and artists alike to focus on sex and the sexual, as well as other topics of social, but not overtly political, interest. In effect, the press became “magazine-ized”, pushing forward fluffier and flashier stories, and reflecting both the constraints of the military regime’s censors and the broader neo-liberal push towards a consumer society.

“Enough background already!”, you shout. True, it’s time to look at how exactly Eşim ve Ben fits into this entire scheme of events. The series is far from the model set by the Encyclopedia Britannica. Pulpy and flimsy, these issues reflect much more the magazine orientation of the press in the early 1980s than any sort of academic publication. But that doesn’t mean that the editorial team’s approach was any less rigorous. The 24 volumes in the series cover a wide range of topics relating to sex and human sexuality, from sex distinctions (Issue 1) to sex in cinema (Issue 24), and orgasm (Issue 6), pregnancy (Issue 9), and sexual research (Issue 16) in between. Some of the information provided in the texts is clearly scientific or sociological in nature, while other narratives are anecdotal or titillating in both their substance and style.

The cover of Issue 19, devoted to “prostitution, trafficking of white women, brothels, and the gigolo trade.”

Prostitution

Pioneers in prostitution

Temple sex workers

A small history of sex work

Sex work in Ancient Greece

Sex work in Rome

Sex work in Mediaeval Europe

Sex work in modern Europe

Male sex workers

Gigolos and sex worker-client relations

Trafficking of women and street-involved sex workers

Brothels

An article on virgin sex workers.

Eşim ve Ben surprises in a number of ways. One is its use of language, which appears to air on the side of the less offensive. I’m not a sociolinguist, and I can’t provide any sort of breakdown in terms of the register used and the relative offense that might have been caused given the time period in which the publication was produced. But there are some noticeable phrases that point to a particular mindset or ideological standpoint. Issue 19 is devoted to “Fahişelik-Beyaz Kadın Ticareti-Genelevler-Jigololuk” (“Prostitution – Trafficking of White Women – Brothels – The Gigolo Trade”). Similar to Anglophone communities, the preferred terminology employed by contemporary Turkish activists for these sorts of activities is seks işçiliği (literally “sex work”), which emphasizes the fact that they are types of labour. The terms employed by the contributors are certainly not towards the extreme offense end of the spectrum of terminology for sex workers or their places of work, but they do indicate a particular stance that seeks to exclude sex work from more general discourse about labour and labour rights. Indeed, the broader discussion of sex work is one that smacks of a patriarchal and patronizing attitude intent on casting the sex worker as a pathetic individual devoid of autonomy or love, doomed to provide the rest of society with a necessary but unsavoury service.

It would be easy to dismiss such attitudes as being the product of a bourgeois or right-wing mentality, but the truth of the matter is that these strains of thought were far from uncommon among male members of far-left groups in the 1970s. I explored these types of misogynistic attitudes in a presentation on the Türkiye İhtilalci İşci Köylü Partisi (TİİKP) at the University of Sheffield in 2014. Eşim ve Ben goes even further by showing that they were not just restricted to views about women, but were also encapsulated in discussions of sexual diversity. Issue 19 makes a clear distinction between “erkek fahişeleri” (“male prostitutes”, meaning gay men who have sex with men for money) and “jigolo” (the “gigolo,” usually a straight man who provides companionship and sexual services to women as part of a financial transaction). The article on the former quickly descends into a discussion of homosexuality as a whole, and the wretched nature of many homosexuals (presumably the catalyst for male prostitution). The one on gigolos, in contrast, speaks of their glamorous lifestyles among the rich and famous. The article admits that some gigolos are bisexual or gay (including in their financial transactions) and that some women provide similar services to wealthy lesbian clients. But neither appear to imply any sort of moral or psychological degradation, as witnessed in the discussion of “male prostitutes”.

The cover of Issue 20, devoted to “sexual deviations, homosexuality, sadomasochism, fetishism, and exhibitionism

On “sexual deviations”

The psychological roots of deviations

Homosexuality

Fetishism – featuring Mick Jagger

Fetish imagery

Exhibitionism

Famous homosexuals

More famous homosexuals

Even more famous homosexuals!

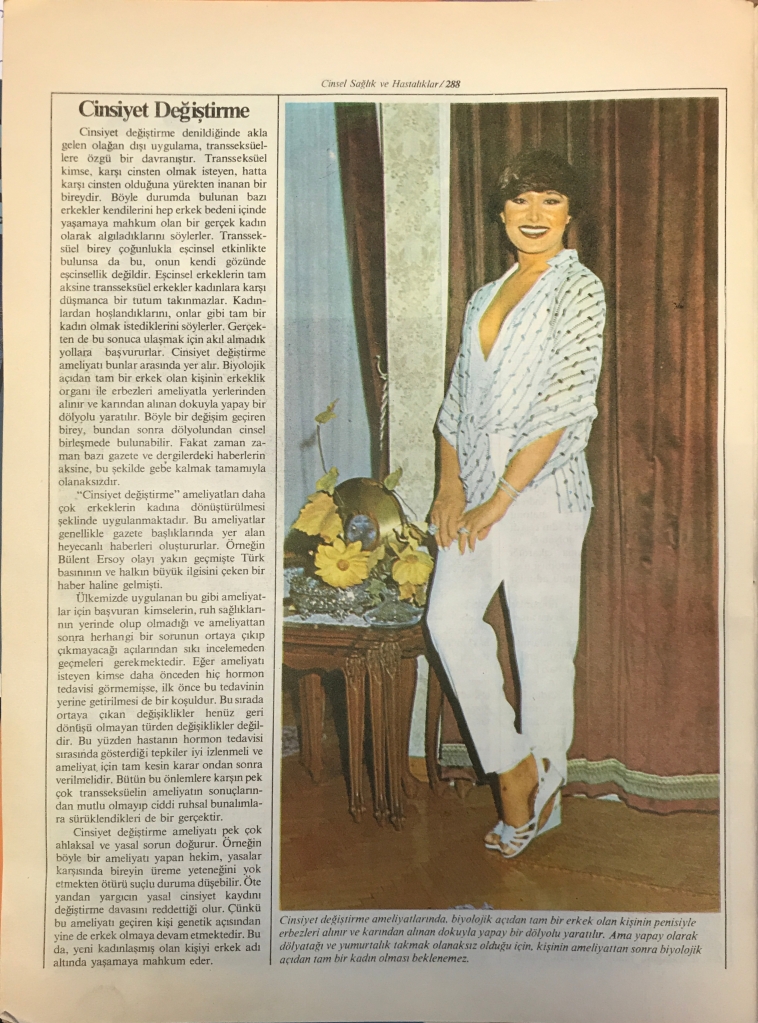

Patronizing and exoticizing language is a feature in many of the other Issues as well. Issue 20 focuses on “Cinsel Sapmalar-Eşcinsellik-Sadomazohizm-Fetişizm-Teşhircilik”(“Sexual Deviations-Homosexuality-Sadomasochism–Fetishism–Exhibitionism”). Beyond the use of the term “sexual deviations” to denote sexual pluralism, the lumping together of homosexuality, sadomasochism, fetishism and exhibitionism leaves us with no doubt that the contributors viewed them as equivalent and bounded topics. It obscures the fact that homosexual masochists or lesbian exhibitionists find themselves in overlapping but distinct areas of human sexuality, linked to but different from heterosexual aficionados. Much of the material here is tantalizing and intended to shock and excite, with pictures of women in leather harnesses, loosely draped towels, and black-lace stockings abounding. Similarly, Issue 12, which focuses on sexual health, and includes a small section on trans people and transitioning, wastes no time in providing an expert overview of patronizing attitudes about trans people’s lives, loves, and perspectives. After attempting to strike a positive balance about the desire of trans people to be seen as the gender they express, the composer of the article quickly launches into the psychological, emotional and legal problems faced by those seeking gender reassignment therapy. The article ends with a call for greater research on the impact of these procedures, rather than a sustained effort against rampant transphobia.

Cover of Issue 6, discussing sexual intercourse, sexual gratification, and the orgasm in women and men

Oral sex

Cunnilingus

Kissing

Anal sex

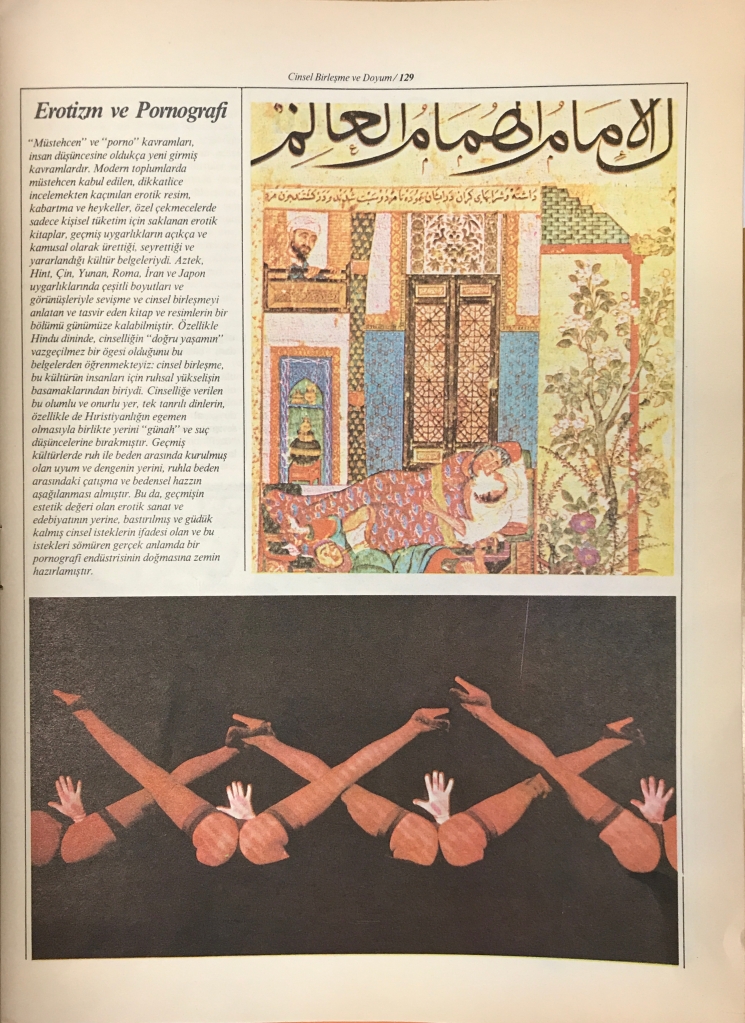

Eroticism and pornography

Sexual love among physically disabled people

It would be unfair, though, to paint this entire project as one of exoticism and fetishization; the creation of an encyclopedia of sex to arouse and excite masses of straight cis-men. The 24 Issues do carry quite a few examples of language and content that is informative, positive and sensitive when dealing with topics otherwise taboo or maligned. The sustained use of the term “eşcinsel” or “same-sex”, as opposed to more offensive or gender-specific terminology is one example (a more comprehensive glossary of LGBT+ terminology in Turkish can be found through the NGO KAOS GL). So too is the pervasive theme that sex and sexuality are core components of all societies across time and space, and that non-conformist sexuality should be understood, rather than immediately shunned and moralized. It even introduces the idea of internalized homophobia, and the intense and long-lasting damage caused by prejudice and exclusionary customs and legislation targeted at queer people. Issue 6, which deals with “Cinsel Birleşme-Cinsel Doyum-Erkekte ve Kadında Orgazm” (“Sexual Intercourse-Sexual Gratification-Orgasm in Men and Women”), explores a variety of penetrative and non-penetrative sexual acts between men and women, as well as other phenomena of sexual excitement, such as pornography. An article in the Issue looks specifically at the topic of “Bedensel Özürlü Kimselerde Cinsel Aşk” (“Erotic Love Among Physically Disabled People”). It’s not my place to say whether the language used is sensitive. But I do believe that the contributors’ decision to feature such topics, and to explore the emotional, psychological and sexual needs and desires of disabled people as part and parcel of human sexuality, does speak to the bona fides of the encyclopedia as making a serious attempt at opening and expanding popular discourse on otherwise taboo topics (check out Disability After Dark if you’re interested in just how far this erasure usually goes).

Start of article on AIDS

Continuation of article on AIDS

Another aspect of this (quasi-?)progressive attitude is Issue 12’s feature on AIDS, “our age’s new illness” (“Çağımızın Yeni Hastalığı: AİDS”). Perhaps I’m swayed by Russell T Davies’ superbly devastating mini-series It’s a Sin, but I do believe that the inclusion of the piece speaks to both the foresight of the contributors in terms of public sexual health, and their temerity to discuss topics that most governments and institutions would have preferred to see swept under the rug. The original article would have likely been drafted in 1982 or 83, one or two years after the illness was first named, and two or three years before the first case was identified in Turkey, according to a report by the HIV/AIDS NGO Pozitif Yaşam. The article makes no bones about homosexual men being the worst affected group, but it does so without resorting to imagery of fire and brimstone to explain the reasons behind this course of events. While moralizing to a certain degree, particularly in terms of some gay men’s propensity towards multiple sexual partners and anonymous sexual relations, it aims to educate through science and experience, rather than scaremongering. This is remarkable, given that it was only in 1985 that Turkey’s Health Ministry issued official regulations on the illness, meaning that the authors of the piece would have had to source their material from abroad, rather than relying on local sources and discussion.

This, of course, raises an interesting question about the origins of some of the content in Eşim ve Ben. The article on HIV/AIDS contains a fair number of statistics relating to infections in the United States, but nothing to do with the potential for its spread in Turkey. This is understandable, given that the illness only started to capture the imagination of the country’s press in 1985, according to the overview of HIV/AIDS in the Turkish press from Medium.com by Ceviizcom. But other articles also demonstrate a heavy reliance on Euro-American sources. The studies and scholars most frequently cited across the 24 Issues are usually well-known cis white men, usually from Europe or the US. Kinsey, Freud, Maslow, and Reich all come up, and the volume packed with information on sex studies and research is largely an overview of the scholarship produced in Euro-American academia. Even more intriguing is the geographical approach taken in Issue 17, which looks at sex throughout history, and in Issue 18, where sex and society are problematized. Clearly North Atlantic-centric, it focuses on European societies (subsuming, in its path, ancient Egypt, Palestine, and Greece) as well as a few other civilizations deemed to be of import, such as ancient China and India. I find the use of the term “Judeo-Christian” across the series to be of particular interest, given its own troubled history, and the manner in which it has responded to Euro-American political interests, as so deftly outlined by Dr. Mark Silk in the National Catholic Reporter and Dr. James Loeffler in The Atlantic.

Cover of Issue 17 on sex in history

Sex in the pre-historic period

Sex lives of ancient Palestine

Issue 18, devoted to society and sexuality, sexual oppression, morality, and virginity

Society and Sexuality

Continuation of Society and Sexuality, including image of Queer Jewish group in the US

Sexual morality: “natural” and “unnatural”

Sexual oppression

Islam and sexuality

Continuation of “Islam and Sexuality” and Non-Judeo-Christian Cultures

Incest

Indeed, the contributors’ entire approach to Islamic societies both past and present is exceptionally curious. They do feature in both Issues 18 and 19, but are treated largely as foreign entities, unrelated to the culture and history of the public to which the publication is addressed. The Ottomans appear very briefly in a discussion of sex in “İslamiyet ve Cinsellik” (“Islam and Sexuality”), but only as a source of sexually-charged illustrations and paintings, not as actual sexual beings engaged in the practices described throughout the rest of the series. Islam is often placed into contrast with Christianity and, to a lesser extent, Judaism, rather than assessed on its own, and there is little to no attempt at appealing to lived experiences of readers, many of whom would have likely been Muslims, and thus would have had personal understandings of sexuality and the expression of faith in Islam. It is as if the contributors preferred to treat Muslims as a conceptual category, rather than an amorphous mass of people linked by faith, yet differentiated by a myriad of other experiences, beliefs, circumstances, and desires.

This is not, in some ways, all that unexpected. Şimşek hints at it in his piece, but no shortage of scholars in Turkey and abroad have pointed to the classist, colourist, racist, and orientalist tinges that can be found in feminist, LGBTQ, and other Turkish social movements since the 1980s (and, of course, around the world). Dr. Deniz Kandiyoti (“Emancipated but Unliberated? Reflections on the Turkish Case”), Dr. Yeşim Arat (“On Gender and Citizenship in Turkey”), and Dr. Ruth Miller (“Rights, Reproduction, Sexuality, and Citizenship in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey”) have all driven home the profound impact that white, middle- and upper-class women have had on the composition and direction of Turkish feminist movements since the 12 September Coup. There were, of course, still feminist movements that espoused intersectionality and understood liberation as something that would have to occur on all levels – social, economic, gender, sexual, and political – for it to occur fully on any. But the sexualities and sex lives of women in Istanbul’s cosmopolitan secular communities were and are obviously quite different from those of women in Turkey’s east (as Pınar İlkkaracan and the Women for Women’s Human Rights organization explored in their 1998 paper). It is hard to see how the contributors to Eşim ve Ben could have been writing for both groups. The publication has a clear inclination towards the former, rather than the latter, not least given the preponderance of imagery from New York, London, Paris and Berlin, and the absolute dearth of representation of women and men in Diyarbakır, Ankara or Gaziantep.

Let’s reel ourselves in for a moment, as Eşim ve Ben’s lack of a broad representation does not mean that it fails to reflect a uniquely Turkish perspective. True, there are many articles that tell us more about sex in Europe or the US than they do about Turks’ sexualities. I suspect that any articles entirely in italics are translations, while those in regular fonts are original compositions. But even in those Issues that feature heavily generalized information or Euro-American sources, we can find pieces that stand truly in a local position. Issue 12’s article on gender reassignment is a case in point. Among the generic discussion of desire and difficulties, the author sought to contextualize the excitement that accompanied gender reassignment therapy in the 70s and 80s by reminding readers of Turkey’s most famous trans performing artist, Bülent Ersoy. The snippet is small – only half a paragraph – but it’s a clear indication of place and time; an aide memoire for the audience that this isn’t quite as foreign to them as they might think.

It’s no secret that I think periodicals are fascinating pieces of pop history. Sometimes it’s easy to see their role in the evolution of society, and sometimes it takes a bit more scratching and analyzing to get to the root of the matter. The brief mention of Bülent Ersoy might not be much, but it’s part of the proof that Eşim ve Ben was more than just titillation or translation. It was an attempt at transforming, however slowly and minutely, the discussion of sex and sexuality among a section of Turkish readers. And the context in which the publication appeared brings home the ingenuity and resourcefulness of those who opposed and subverted, whatever restrictions they might face.

Neither Eşim ve Ben nor Görsel Yayınlar achieved the heights of Dr. Ruth in terms of popularizing and demystifying discussions around sex. But they did break taboos through their publications, and so were revolutionary in their own way. By our remembering and revisiting them, we remind ourselves that talking about sex and sexuality can tell us a whole lot more about ourselves and the societies that we live in than might be apparent at first blush.

Leave a comment