As Jews, we often operate in two overlapping, but distinct cultural realms. Growing up in Canada, my sisters and many of my friends had two names: an English one and a Hebrew one. I was lucky to have a name that worked in both languages, but those who did have two monikers were none the poorer. They were markers of our double belonging. I never learned Hebrew, and we only spoke English at home, but these and dozens of other Hebrew or Yiddish words and phrases – Ladino ones for our Sephardi brethren – became part of a system of shibboleths marking our Jewishness, no matter what degree of integration we might have achieved. They might occasionally cause embarrassment, but for the most part we took it as a given that they were simple facts of our identity. It was, and is, similar to how children in many minority communities around the world learn to navigate growing up as the Other in a society focused largely on the experience of the majority.

The British Library collections mirror these sorts of distinctions, albeit in a bit of a roundabout manner. The Hebrew Collections feature tens of thousands of examples, both exquisite and mundane, of Jewish creation inside Jewish communities. Written in Hebrew, Aramaic, Ladino, Yiddish, Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Persian, Zarphatic, Judeo-Italian or any number of other Jewish languages and ethno-lects, these are self-consciously Jewish works. There is a whole other selection of “Jewish” works, however, scattered throughout the rest of the Library’s holdings. Some of these are works about Jews written by non-Jews; attempts by Goyim to describe our communities and our culture, for better or for worse. But many others are written by Jews about themselves, or about completely unrelated topics, in the languages of the majorities amongst whom they live. These represent the contributions of Jews to the broader societies in which they participate. The Library’s Hebrew Manuscripts: Journey of the Word exhibition looks at a number of items from the former group of works. In this blog, I’m going to explore a few points in Jewish history in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey, guided through the latter class of creations in the Turkish and Turkic collections that I curate.

As always, a few caveats are in order. Jews around the world are tied together through religious and textual traditions, including that of Diaspora. In recent years, we are also increasingly tied together through marriage and greater mobility: my extended family counts members from Belarus, Hungary, India, Morocco, Yemen, Brazil, and Poland, all of them Jews (plus lots of non-Jews from Russia, Nigeria, Jamaica, Canada, Indonesia, and Germany). But our experiences within each of these societies has been markedly different, shaped as much by the internal dynamics of the community as by its relations with the majority, not to mention the broader context of the society as a whole. I am not a Turkish Jew, and my lived experience is not theirs. What follows is shaped greatly by various sources, both Jewish and non-Jewish, of Turkish Jewish history. This has been a learning experience for me, one to reflect against my own life and inheritance, but not to subsume within them. That said, there are lots of great sources on Turkish or Ottoman Jewish history available to the Anglophone, all discoverable on WorldCat, and a few of which I’ll point out throughout the course of the blog.

As a final note, I should clarify that I will only be looking at Jews in this post; not the Dönme. The descendants of those Jews who accepted Islam in the 17th century alongside Sabbatai Zevi, Dönmeler are clearly related to the Jewish communities of the former Ottoman Empire. Nonetheless, they have a distinct ethno-religious identity, one with a rich history connected to the evolution of Turkish society. There’s some great scholarship on the Dönme available to English-speakers, including Marc David Baer’s The Dönme: Jewish converts, Muslim revolutionaries, and secular Turks.

The Jewish presence in Anatolia is a long one. After all, the Old Testament clearly shows at least a knowledge of, if not a familiarity with, the region around Mount Ararat in eastern Anatolia. Communities have been documented since the late 4th century BCE, and Romaniote or Greek-speaking Jews were a fixture throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods. Jews’ conditions under the Ottomans both before and after the Conquest of Istanbul in 1453 were complex. It was not, however, an experience of crushing persecution and expulsion, as frequently occurred in Christian realms throughout Europe. Ashkenazi Jews started arriving as early as the 15th century, and a massive influx of Sephardic Jews invited to the Ottoman Empire by Bayezit II following their expulsion under the Spanish Inquisition allowed the community to grow further. Sephardis spread throughout the Well-Protected Domains, with large communities in present-day Bosnia, Bulgaria and Greece, as well as Turkey. The Serbian-Sefardi novelist David Albahari was born in Peć/Peja, Kosova, and my grandfather’s family ended up as far afield as Ukraine. Many of those in the former Yugoslavia and Greece were decimated in the Holocaust. Imperial expansion also meant that Arabic-, Kurdish-, Assyrian- and Persian-speaking Jews became Ottoman subjects as well, all leading to an Ottoman Jewish millet that was staggering in its diversity.

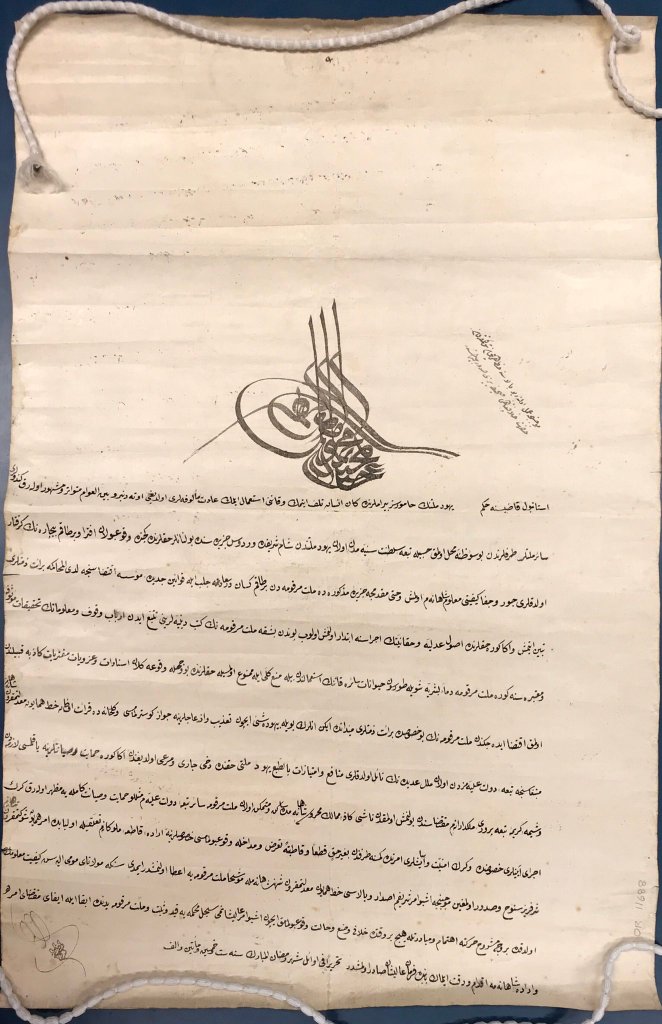

Cohabitation wasn’t always an easy affair. Or 11688 is a firman issued by Sultan Abdülmecit I in 1256 AH (1840 CE) ordering the Kadı of Istanbul to protect the city’s Jews following anti-Jewish violence in both Rhodes and Damascus. The firman was a response to riots motivated by the Blood Libel; an anti-Jewish trope that has long been common in Christian European states. Although changing each time it appears, the Libel is broadly based on the lie of Jews’ use of Christian blood in their rituals. Most recently, accusations about its recycling in the HBO series Lovecraft Country have surfaced. In both Rhodes and Damascus, the accusations were spread by Christian clergy among the Christian inhabitants. In both locations, European representatives helped lend credence to the claim; a clear contrast to the manner in which central Ottoman authorities sought to stymie its incendiary effects upon inter-communal relations.

An inset of the manuscript showing seals of signatories, along with Ottoman Turkish explanations above them, all written in the same hand (British Library, Or 17004B).

A full view of the Ottoman petition from the notables of Basra regarding corruption and mismanagement in the city (British Library, Or 17004B).

Another example of interaction between Jewish subjects and non-Jewish authorities found within the Turkish collection comes from late 19th-century Iraq. Or 17004 is a bundle of documents that are primarily administrative in nature, usually petitions by various local notables to Ottoman officials. One, Or 17004B, stands out for its sheer length as well as its impressive number of seals. A letter of complaint to the Ottoman capital regarding corruption and the poor provision of municipal services in Basra, the document contains almost 100 seals of politicians, religious leaders, businesspeople and other notables. Two of these are in Hebrew script and are from to Jewish signatories to the protest. One of them belongs to Yitzhaq Senyor, Arabized as Yusūf Sinyor in the caption above the seal, while the other is of Shantub Eliyahu. The second Hebrew seal is slightly smudged, making it difficult to see the exact spelling of Shantub’s name and whatever other information it might have included. They exemplify the inclusion of Jewish citizens and subjects into the daily fabric of Ottoman life, whether in the centre or the periphery, as cooperants or opponents of centralized power. The dual names, Hebrew and Arabic, also point to those two, partially overlapping spheres within which most minorities live.

Those spheres, of course, were far from neat and organized. In broader society, Ottoman Turkish would have competed with Armenian, Greek, Arabic and other languages as means of intercommunal communication, all depending on the context in which Jews found themselves. Within the community, however, at least two different sets of languages would often be employed. There were the holy languages of Hebrew and Aramaic, crucial for theology as well as the loftier sciences such as philosophy. But there were also vernaculars, the most common of which, for Jews in Istanbul, Western Anatolia and Rumelia, was Ladino. In the 19th century, the expansion of printing technologies and literacy meant that more was being published in Ladino than ever before.

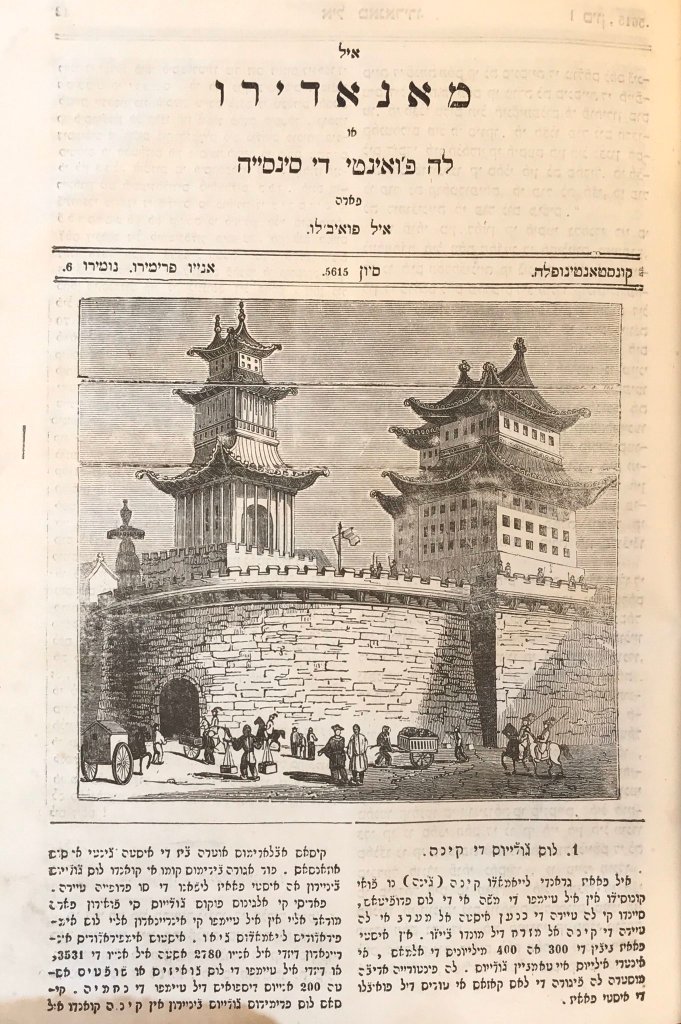

Similar to other non-Muslim communities in the Empire, however, this also provided an entry point for European missionaries to exploit vernaculars in the hope of gaining converts. The periodical El Manadero, o la Fuente de Sensya para el puevlo is a case in point. It was published in Istanbul between 1855 and 1858, first by the Scottish Mission and then by Mose Penah. The magazine features pieces on science and general knowledge as well as Judaism. It exemplifies how non-Jews have occasionally made use of the vernacular to enter our spaces, often targeting us for conversion, a process that continues to this day. Whatever their intentions, one of the (perhaps unintended) impacts of these missionaries was the growth of Ladino and Jewish publishing in the city. That much is clear from a number of sources, such as Rachel Saba Wolfe’s piece on Protestant Missionaries producing Jewish texts, or Rachel Simon’s 2011 work on the impact of Hebrew printers on Ladino culture in Istanbul. This reclaimed activity laid the groundwork for a tradition that has continued to this day, albeit on a smaller scale, in the form of the Şalom newspaper or online in AkiYerushalayim.com.

The spheres of Ladino usage, and Jewish culture in general, grew apace through the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th. The Alliance israélite universelle, a French Jewish organization, opened a number of schools for Jews across the Ottoman Empire, introducing French as a new language of Ottoman Jewish expression and interaction. Jews also rose, thanks in part to a burgeoning Ottomanist identity, into the professions and the bureaucracy. In his groundbreaking 1963 study of interactions between minorities and the Committee of Union and Progress (İttihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti, CUP), Feroz Ahmad has explored just how actively Jews sought political agency through nominally pan-Ottoman organizations, rather than their own parochial ones.

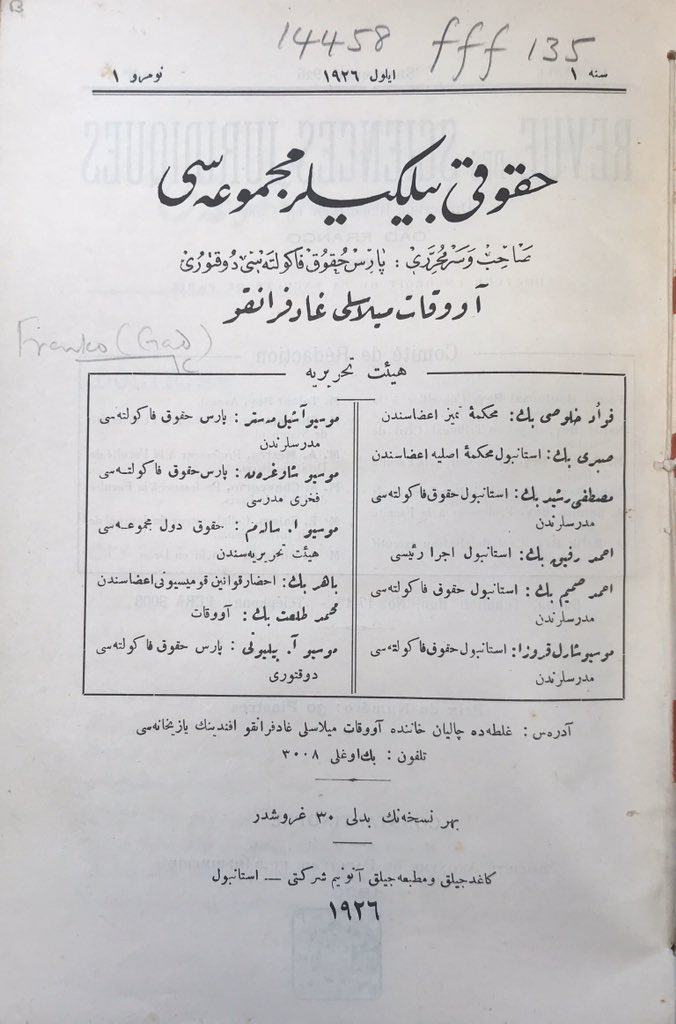

A number of Jews achieved particular prominence; Ahmad provides a handy overview of some of the most active. One of those not mentioned in his work was Milaslı Gad Franko. Born in Milas near Izmir, he was a teacher, journalist and ardent supporter of the Committee of Union and Progress (İttihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti) before becoming a lawyer. He worked tirelessly in the interest of the new Republic; most recently, Tahir Kodal has provided a comprehensive overview on his interventions regarding the status of Mosul. In 1926, Franko began publishing the Hukuki Bilgiler Mecmuası (Legal Sciences Journal), a review of legal thought, philosophy, and history in Turkey. The Library holds the entire run of these publications, which demonstrate Franko’s deep commitment to the Turkish legal community and the development of jurisprudence within the Turkish Republic.

The start and end dates of Franko’s publication point to two particularly important changes of era for Turkey’s Jewish community. Three years before the Mecmuası appeared, in July 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, formally ending the conflict between the Ottoman Empire on the one hand and Greece, Italy, France, Romania, Japan, Yugoslavia and Great Britain on the other. As part of the Treaty, Jews, Armenians and the Greeks of Istanbul became recognized minority communities in the Ottoman Empire, to be granted particular group rights and privileges. The Empire became the Republic on 29 October 1923, and two years later, Jewish leaders announced their intention to give up the rights and responsibilities afforded to them by the Treaty of Lausanne. Reyhan Zetler has provided an in-depth exploration of the period and the reasons for this decision, which you can read in full here. The main thrust of the argument put forward by a number of intellectuals was that Jews would prefer to benefit from the Republic’s commitment to laicism, rather than organize their own affairs as a separate religious community.

The 1930s produced mixed results for Jews in the new Turkey, now full citizens without distinction – at least in law – from their Muslim co-nationals. Some intellectuals fully embraced their status, similar to Milaslı Gad Franko, integrating into the new structures of the nationalist nation-state. A few, such as Munis Tekinalp (Muniz Cohen), became ardent Turkish nationalists. The collections of speeches made to the First History Congress (1932) and the Second History Congress (1937) demonstrate this. Both include presentations by a number of Jewish intellectuals who contributed to the articulation of the Turkish History Thesis, a metanarrative of Turkish origins and nationhood. Avram Galanti in particular was a prominent speaker, clashing with a number of other scholars on ancient history and relative input of the Semitic nations into Classical civilizations. And while there is plenty of anti-Semitism on display at the Congress, it is directed much more towards Arabs – considered by many nationalists as traitors to the Ottoman cause – rather than Jews. Indeed, Central European Jewish intellectuals were welcome to speak at both events. Following the rise of Nazism and anti-Jewish legislation across Europe in the 1930s, a number of German and Austrian Jews were even given refuge in Turkey, and helped to reshape the country’s higher education system.

But nationalism also led to a backlash in a different way. From the late 1920s through the 30s, the Vatandaş Türkçe konuş! (Citizen, speak Turkish!) campaign pressured minorities to use Turkish, rather than their mother tongues, in public and private life. Although not overtly targeted at them, the Ladino-speaking Jews took a considerable amount of heat, as Rıfat Bali explores in this piece. It should not be a surprise that usage of the language declined considerably throughout the 20th century. In 1934, a series of pogroms in Turkish Thrace led to assaults on Jews, the destruction of property, and the flight of some 15 000 people out of the region. In 1942, the year Franko’s journal ceased publication, the most damaging of all steps were taken with the imposition of the Varlık Vergisi (Wealth Tax). The tax was levied on fixed assets with the stated goal of filling the state’s coffers in the event it should be dragged into the Second World War. In practice, the differential rates applied to the country’s various religious and ethnic communities effectively destroyed minority capital. Muslims paid a rate of 4.94%, while the one levied against Greeks was 156%; Jews 179%; and Armenians a whopping 232%. Many were destroyed financially and a number of people committed suicide. Those who could not pay the tax were sent to labour camps in Eastern Anatolia, and their families were laden with their debts. The Varlık Vergisi was repealed in 1944, but compensation was not paid, and many Jews – similar to their Armenian, Greek and Dönme co-nationals – hesitantly rebuilt their lives in Turkey from scratch.

The post-War period saw a number of changes to Turkish society and the region that altered Jewish life in the country, as reflected in the Library’s collections. The creation of the state of Israel in 1948 added a new route of emigration for some Jews, as it did for those living in many other countries. This was occasionally spurred by bouts of political and economic turmoil, especially as the country went through coups in 1960, 1971, 1980 and, by memorandum, in 1997. The anti-Greek riots of the 1950s, although not directed towards Jews or Armenians, could not have helped restore the lost confidence of the pre-War period. More recently, the second bombing of the Neve Şalom synagogue in 2003, and periodic incidences of anti-Jewish violence, coupled with the a stifling of public life following the 2013 Gezi Park Protests and the 2016 failed coup, have all left a distinct chill in the air. Marcy Brink-Danan has documented some of the effects of these various pressures on Jewish life and cosmopolitanism in Istanbul up to about 2010.

Despite dwindling numbers, however, Turkish Jews have continued to make an impact on contemporary society in various fields. Dr. Yael Navaro, a social anthropologist currently working at Cambridge University, reflected on her own experience as a Jew in Turkey within the broader context of the state and secularism in her 2002 work Faces of the State: Secularism and Public Life in Turkey. Seven years later, Dr. Leyla Navaro, a prominent psychiatrist focusing on issues of gender, made waves when she wrote an editorial in the now-defunct Radikal newspaper decrying the continued outsider status imposed upon Sephardi Jews in Turkey. The newspaper is no longer online, but you can read the piece here (in Turkish). Navaro’s piece caused such a stir that then-President Abdullah Gül called her to reassure her of the state’s anti-racist commitment.

Perhaps the most prolific producer of publications is Rıfat N. Bali, a historian and author of dozens of articles and books on the history of Turkish Jews. These works appear in both Turkish and English, ensuring that the history, views, and cultural legacy of the community continue to be accessible to those inside Turkey as well as to members of the diaspora. A simple overview of some of Bali’s titles shows their coverage of wide swathes of Turkish Jewish history: The “Varlık vergisi” affair; 1934 Trakya olayları (The 1934 Thrace Events); and Cumhuriyet yıllarında Türkiye Yahudiler (Turkish Jews in the Republican Years). Similarly, the publishing house he helped found, Libra Kitap, has provided a launchpad for many authors to explore these and other themes. Ayşe Gürsan-Salzmann’s Travels in Search of Turkey’s Jews; Metin Delevi’s Türkiye spor tarihinde Yahudi sporcular (Jewish sportspeople in Turkish sport history), and Rey Romero’s Spanish in the Bosphorus are just a few examples of works that have all benefitted from a publisher sensitive to the needs and contexts of the country’s Jewish community.

Today, I continue to acquire works about and by Turkish Jews for the collections I curate. The idea is to do this sensitively, capturing snapshots of Jewish culture in Turkey without turning it into a monolith; reflecting the experiences and contributions of Jews as part of wider Turkish society. In Notes on Camp (in Against Interpretation, and other essays), Susan Sontag reflected on how “depoliticized” camp was a tool for queer men seeking acceptance from straight American society, just as morality had been Jews’ niche in a Protestant United States. The creation of a unique selling point for minorities yearning for tolerance and inclusion is a double-edged sword for many of us looking to live our lives openly, fully and without shame. It highlights our usefulness, but leaves us vulnerable to derision, caricature and erasure. A flattening of our experiences ultimately keeps us trapped in a two-dimensional identity of someone else’s making. By seeking out the myriad of Jewish expressions from Turkey, as well as those of dozens of other ethnic, linguistic, religious, sexual and gender minorities living in the country, we get a far richer, fairer, and truer picture of Turkish society. In this way, we can all encounter more fully the beauty and very-human complexity of Turkish creativity.

Leave a comment