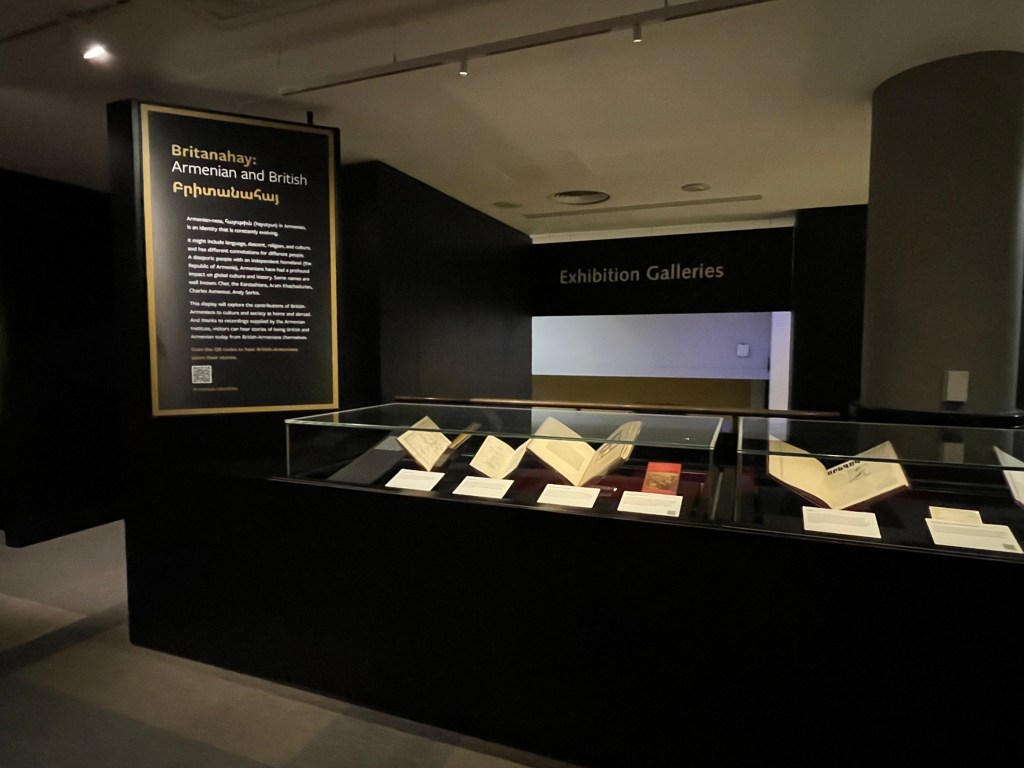

From 27 September 2025 until 22 February 2026, the British Library’s Sir John S. Ritblatt Treasures Gallery offers visitors a unique view onto Armenian-British history. Entitled Britanahay Բրիտանահայ: Armenian and British, the four-case display brings together items from the British Library collection that highlight Armeno-British communities and interactions. What’s more, it’s an interactive experience with QR codes linking to extracts from oral history interviews. These were collected by the Armenian Institute as part of their Heritage of Displacement: Oral History from the UK Armenian Communities (2023-2026) project. The recordings, which bring to the fore the collaboration between the Library and the Institute, connect written word to lived experiences, emphasizing that British-Armenian identity is constantly evolving.

Britanahay acts as a gateway to the world of Armeno-British stories that can be discovered in the Library’s collections. It doesn’t tell the complete history of Armenian communities in the country, or of Armeno-British relations around the world. Accessible and detailed accounts of such narratives can be found in works such as Joan George’s Merchants to Magnates, intrigue and survival: Armenians in London, 1900-2000 and Tigran Tigranean’s Անգլիան եւ հայերը (England and the Armenians). Rather, it invites viewers to understand how they can uncover fascinating accounts for themselves and connect to almost 800 years of shared history.

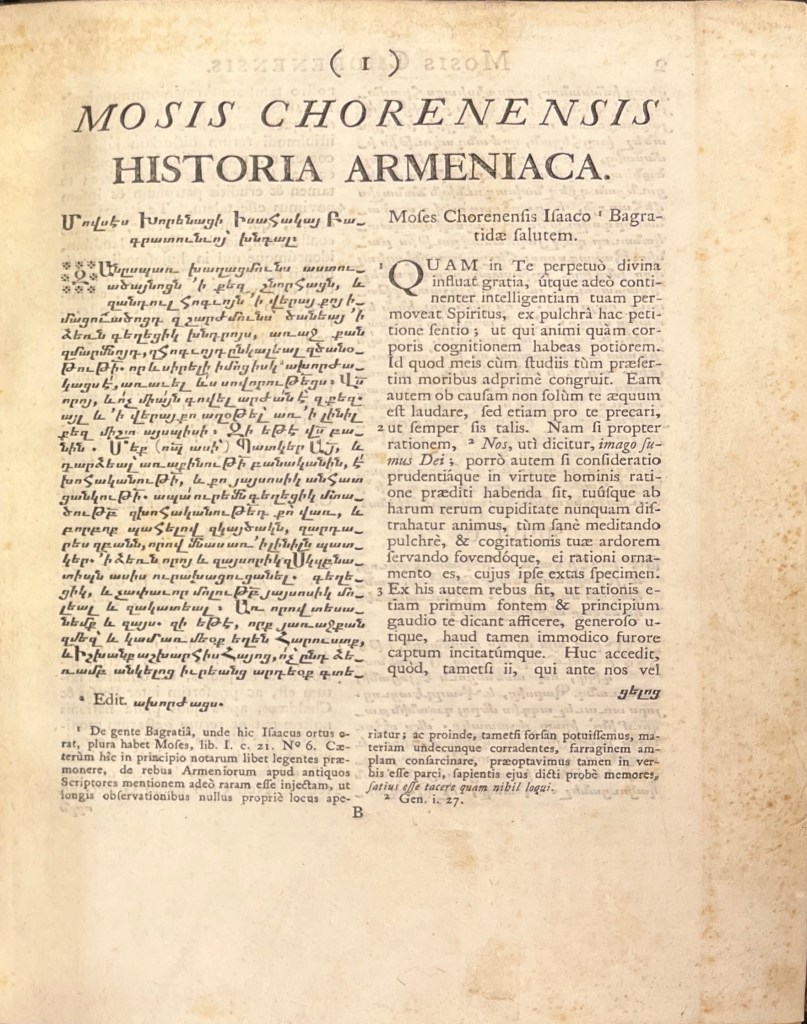

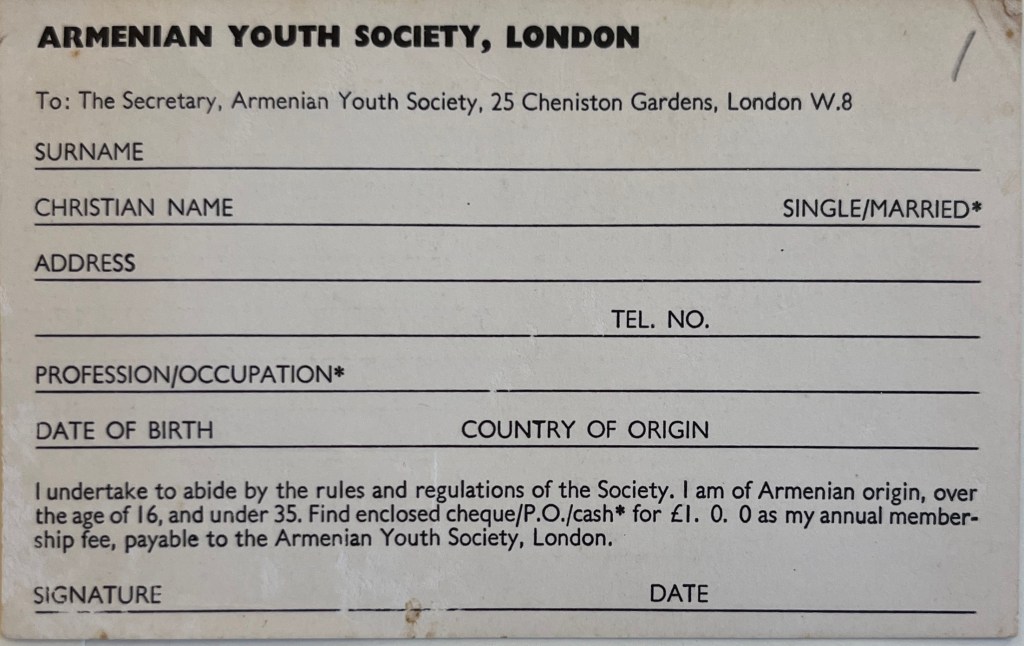

The display is divided into three sections. The first looks at the Armenian presence in this country. It includes a few firsts: the first Armenian book printed in London in 1736 (Movsēs Khorenats’i’s History of the Armenians’/Մովսէս Խորենացիի Պատմութիւն հայոց) and an accounts book from the first purpose-built Armenian cathedral in Western Europe, the Holy Trinity Cathedral, constructed in Manchester in 1870. But this section also includes the material products of more mundane events, such as the publication of the community newspaper Aregak (Արեգակ; Sun) in south-west London in the 1960s and 70s; political advocacy materials from the beginning of the 20th century; and a membership card for the erstwhile Armenian Youth Society.

The second component of the display focuses on Armenian communities in territories under British control. The first interaction of Armenian and English heads of state is evidenced by the exquisite Histoire de l’Angleterre, a French-language manuscript from 1470-80 (Royal MS 14 E IV) that includes an illustration of King Richard II of England meeting King Levon V of Cilicia. The Cilician monarch, ousted from his lands by the Mamluks, had come to Westminster in 1259 to request English and French assistance to liberate Cilicia through a new Crusade. He was unsuccessful, but this beautiful manuscript does lead us to believe that the meeting between the two monarchs was far from tense.

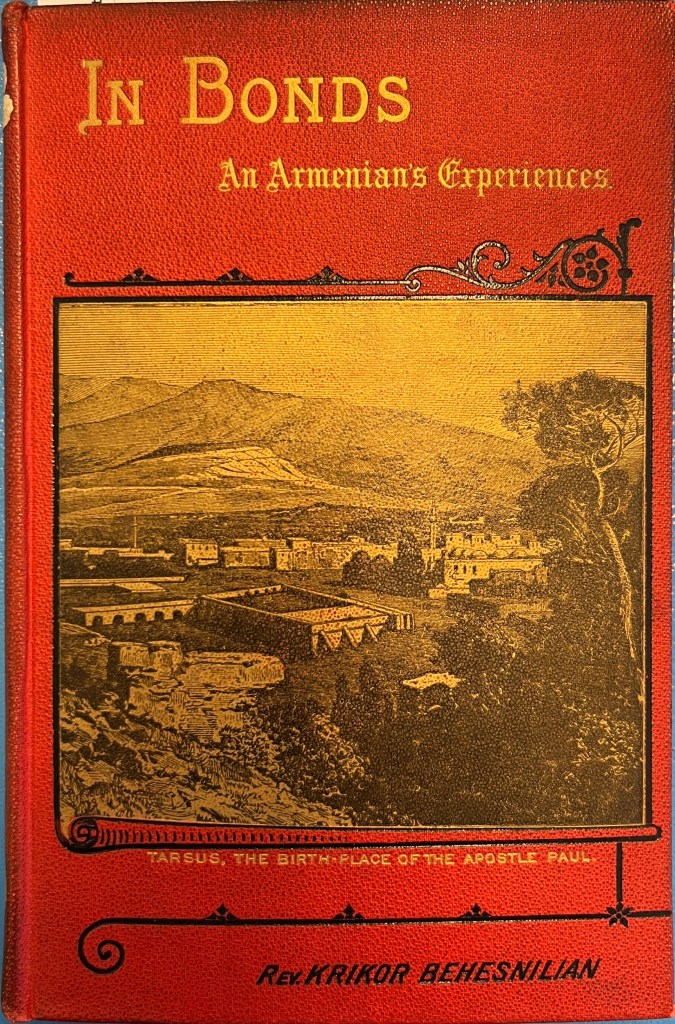

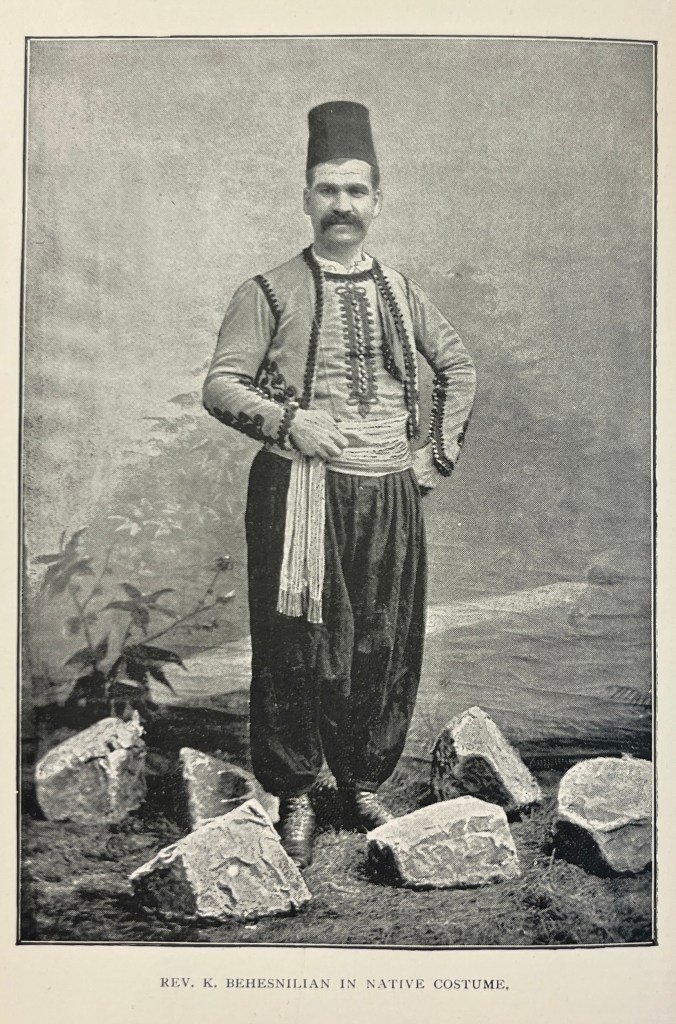

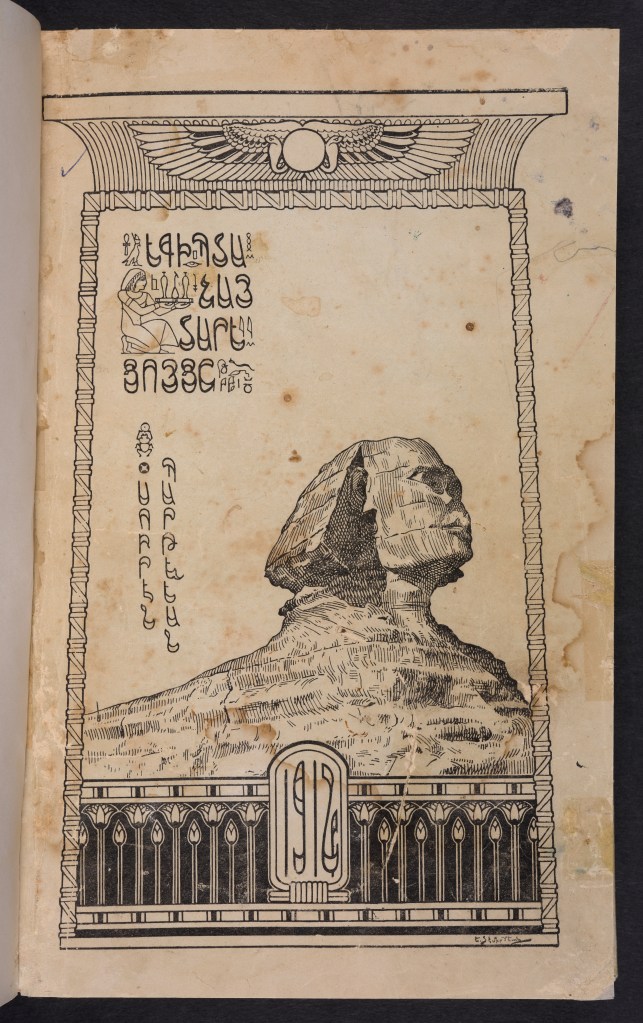

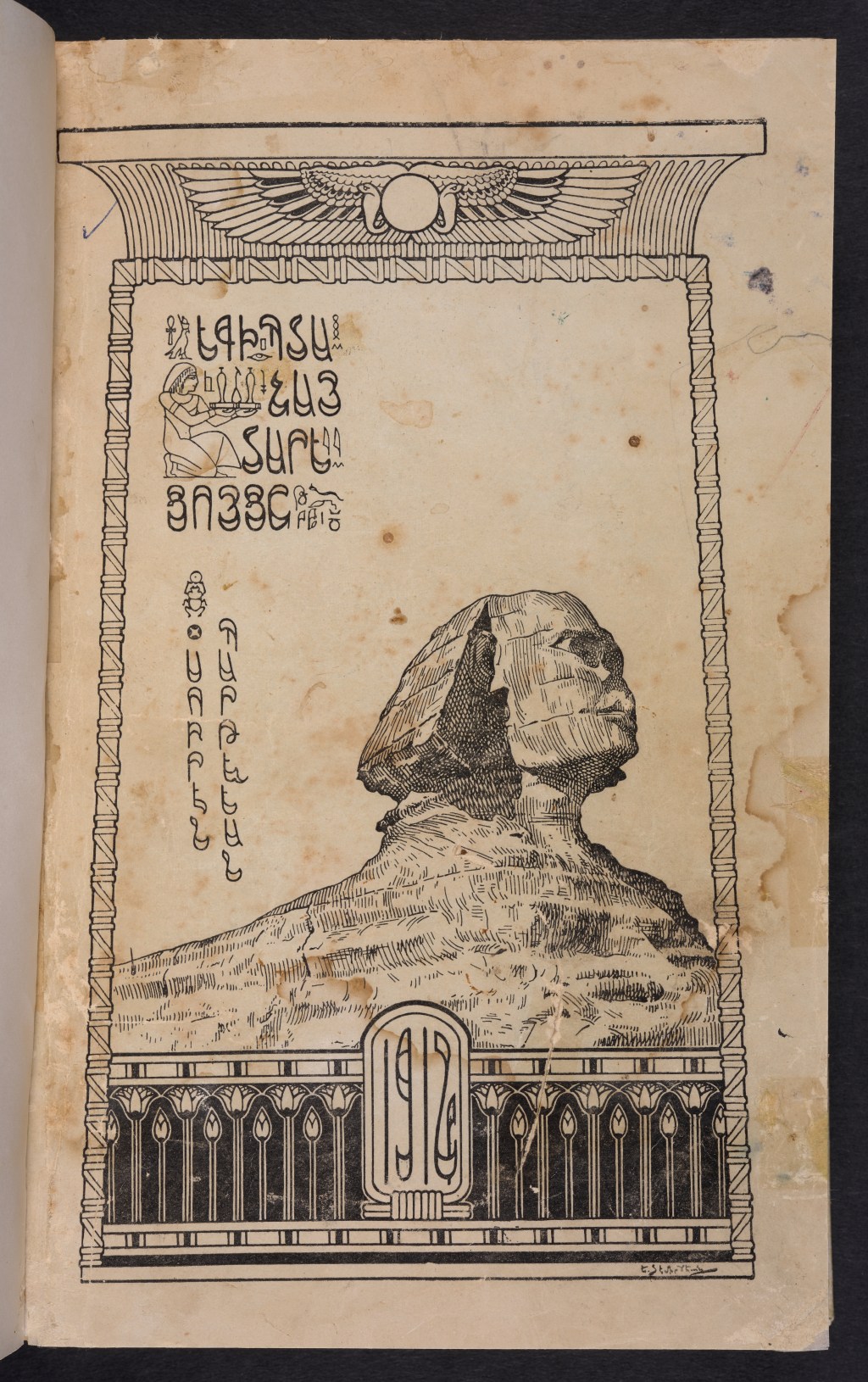

As a diasporic people, Armenians encountered the British across wide swathes of Asia and Africa. In addition to state-to-state relations, this section also speaks to the relationships of Armenian communities and British forces, officials and structures in Egypt, India and Cyprus, among other locations. An Armeno-Egyptian almanac, educational and promotional materials from Cyprus, and a memorial publication of Azdarar (Ազդարար; Advisor) – the first non-English newspaper published in India in 1794 – help spark curiosity about how Armenian communities encountered and adapted to British colonial expansion. Similarly, a translation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet into Eastern Armenian published and performed in Tbilisi in 1889 showcases the impact of British culture on Armenians even outside of British control.

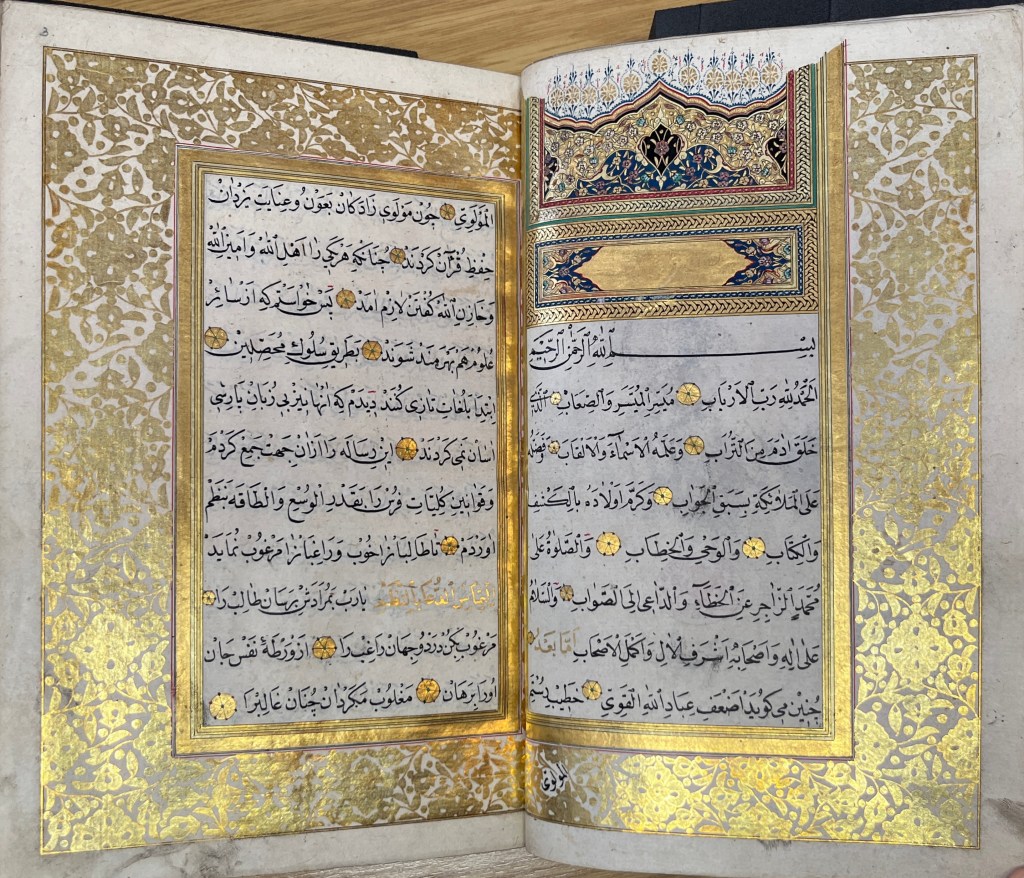

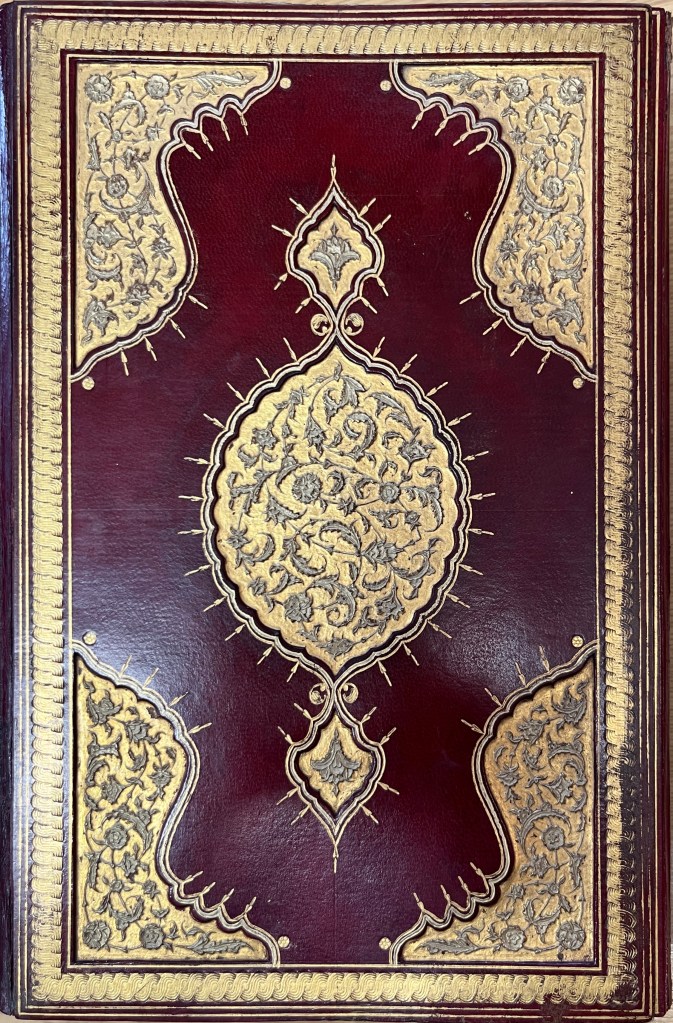

The final case of the display turns the investigatory lens onto the Library itself. Thanks to the groundbreaking work of scholars such as Dr. Talinn Grigor, Dr. Houri Berberian, and Dr. Alyson Wharton-Durgaryan, we are beginning to understand the profound impact of wealthy Armenian mercantile families (Amiras) on the history of collecting and curation at institutions in Western Europe and North America. Names such as Calouste Gulbenkian, Krikor Minassian, Dikran Kelekian and Hagop Kevorkian are well-known in the art world. The extent to which they shaped museum collections, however, is only now becoming apparent.

Two display items explore different aspects of this development. The first is reflected in a beautiful 18th century grammar of Persian in Ottoman Turkish (Or 5097), purchased by the British Museum (the Library’s predecessor) from Dikran Kelekian in 1897. Next to it sits the catalogue Treasures from the Ark: 1700 Years of Armenian Christian Art. This beautifully-illustrated volume, authored by our former Lead Curator of the Christian Orient at the British Library, Father Vrej Nersessian, harkens back to the first flagship exhibition held in the Library’s St. Pancras Building. While referencing the long tradition of religious art among the Armenian faithful, it also points to the many Armenian curators, cataloguers, conservators and patrons who have helped the Library account for its Armenian manuscripts and printed collections.

This brings us back, in many ways, to the core aim of Britanahay. Rather than a rigid narrative, the items on display mirror the breadth and richness of the Armenian holdings at the Library. And the holdings, in turn, do not tell a neat and easily-categorized story because they reflect many lives lived across time and space, with all their messiness and unpredictability. Together, the 15 selected books, magazines and ephemera aim to spark viewers’ curiosity, to excite their minds and senses, and to invite them to further research within our formidable collection. Along with the engaging excerpts from the Armenian Institute’s Heritage of Displacement interviews, they show what fascinating stories the archive can told. All it takes is registering as a Reader, and falling down whatever rabbit hole the catalogue opens up for you.

Britanahay Բրիտանահայ: Armenian and British is open to the public in the British Library‘s Sir John S. Ritblatt Treasures Gallery seven days a week from 27 September 2025 until 22 February 2026. Entry is free of charge.

The display was organized with the participation of the Armenian Institute and the generous support of the Benlian Trust. I would also like to thank the Embassy of Armenia in the United Kingdom, Dr. Zaven Messerlian, Dr. Nazénie Gharibian, Father Vrej Nersissian, Dr. Krikor Moskofian, the Matenadaran, the National Library of Armenia, Holly Kunst and Senem Gökel for their kind and valuable support and assistance.

Leave a reply to Michael James Erdman Cancel reply