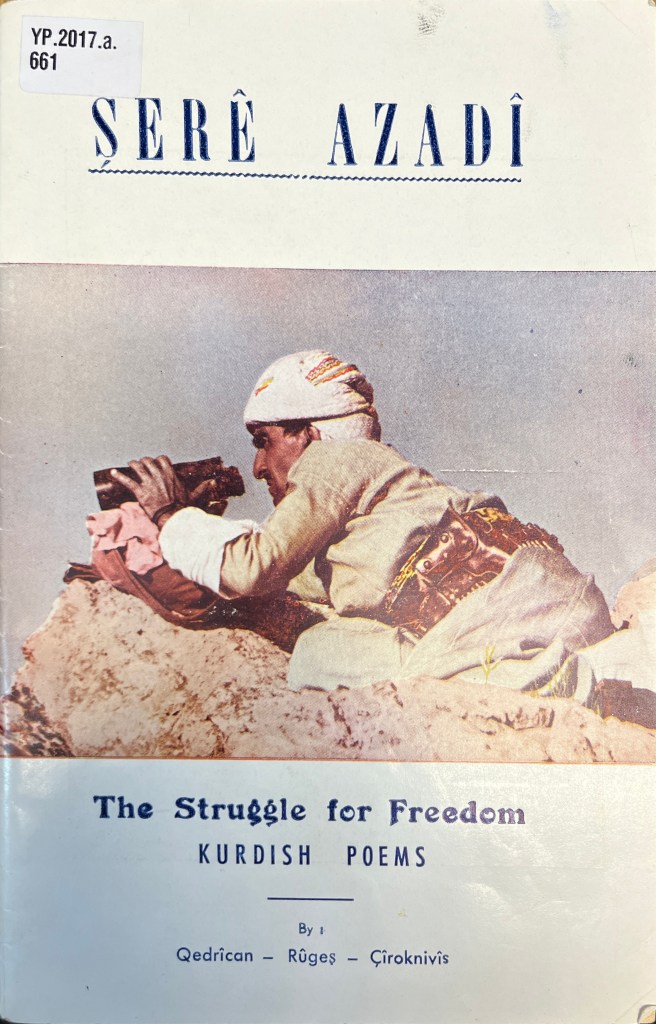

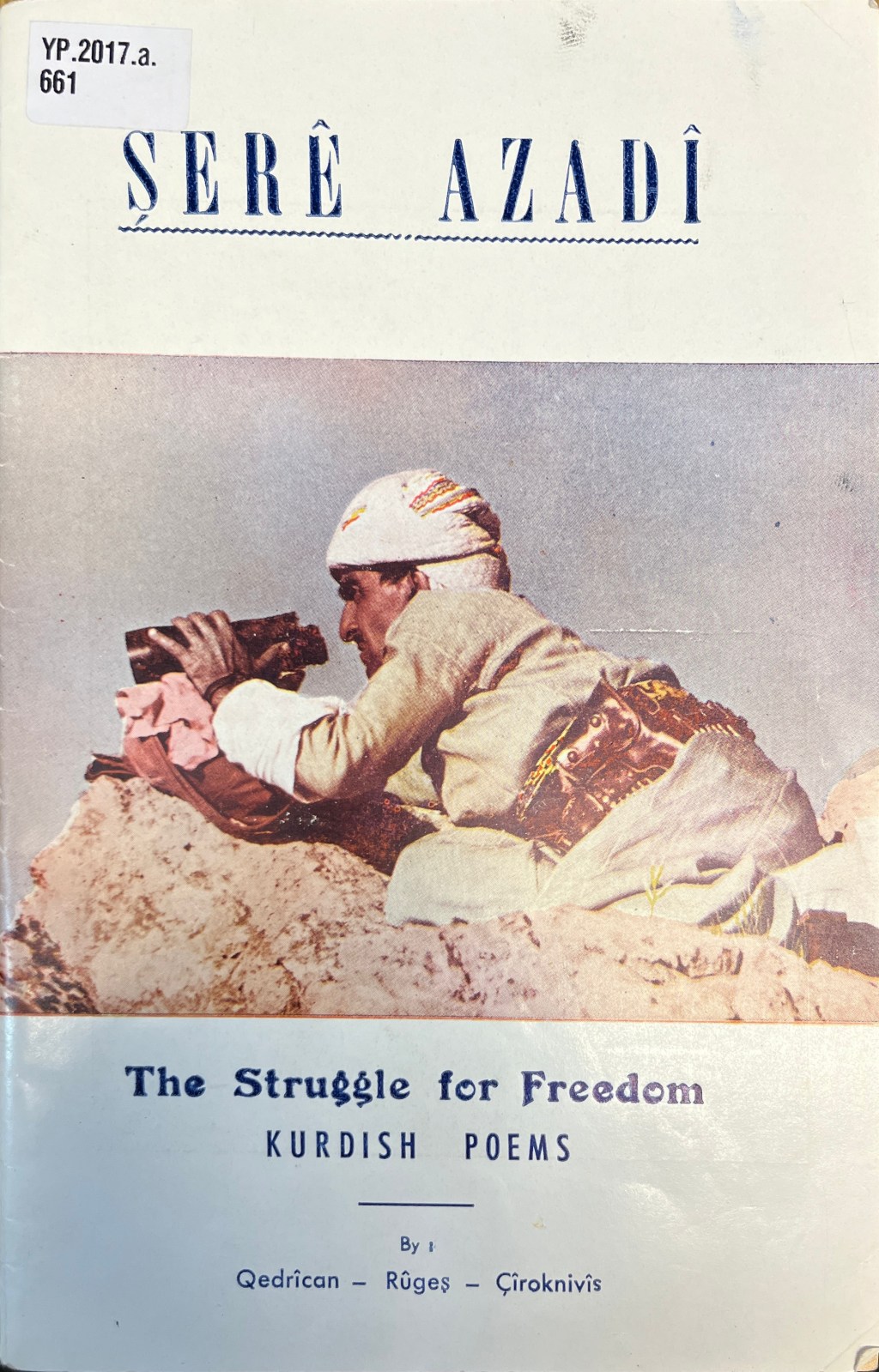

Among the Kurdish works that I catalogued when I started at the British Library in 2016 was a small, flimsy booklet called Șerê Azadî or The Struggle for Freedom, a cheap paperback with catchy photos of Kurdish fighters. WorldCat lists three copies of the publication held at various participating libraries: The British Library, Universiteit van Amsterdam’s library, and that of Universität Marburg in Germany. WorldCat says it was published in Sweden and that’s my fault. If I could redo this (which I can’t) I’d probably put it as having likely been produced in Beirut. A fourth copy held at the Institut kurde in Paris is available through their online repository. Their metadata can’t possibly be correct, as they describe the work as having been published in Damascus in 1956, despite containing dated poetry from 1964. Kurdîpedia has a stub article on it as well, although it looks as though the image they’ve used is from the Institut kurde. Before you start Googling other sources about the booklet, I should mention that this poem is distinct from the 1993 song Şerê Azadî by Koma Azad.

You don’t have to have a great grasp of a language to catalogue materials in it. I will be honest: it was only last year that I started learning Kurmancî seriously (after a lockdown flirtation) thanks to the three-book series Hînker produced by the Enstîtuya Kurdî ya Stenbolê (closed by order of the State in 2016). And now, with the help of Wîkîferheng, I was at last able to enjoy Şerê Azadî.

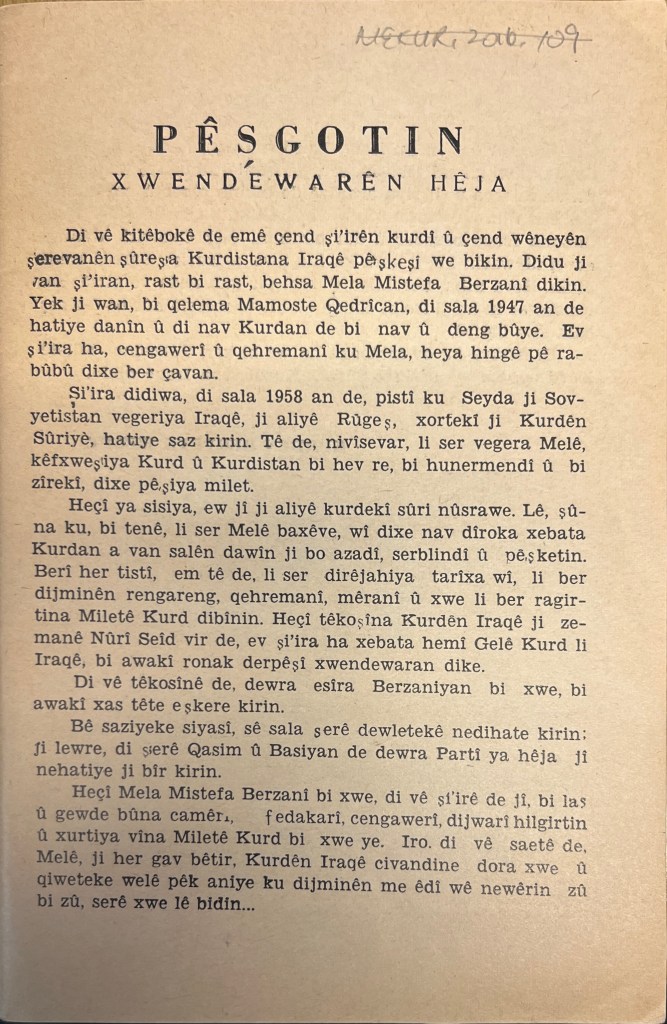

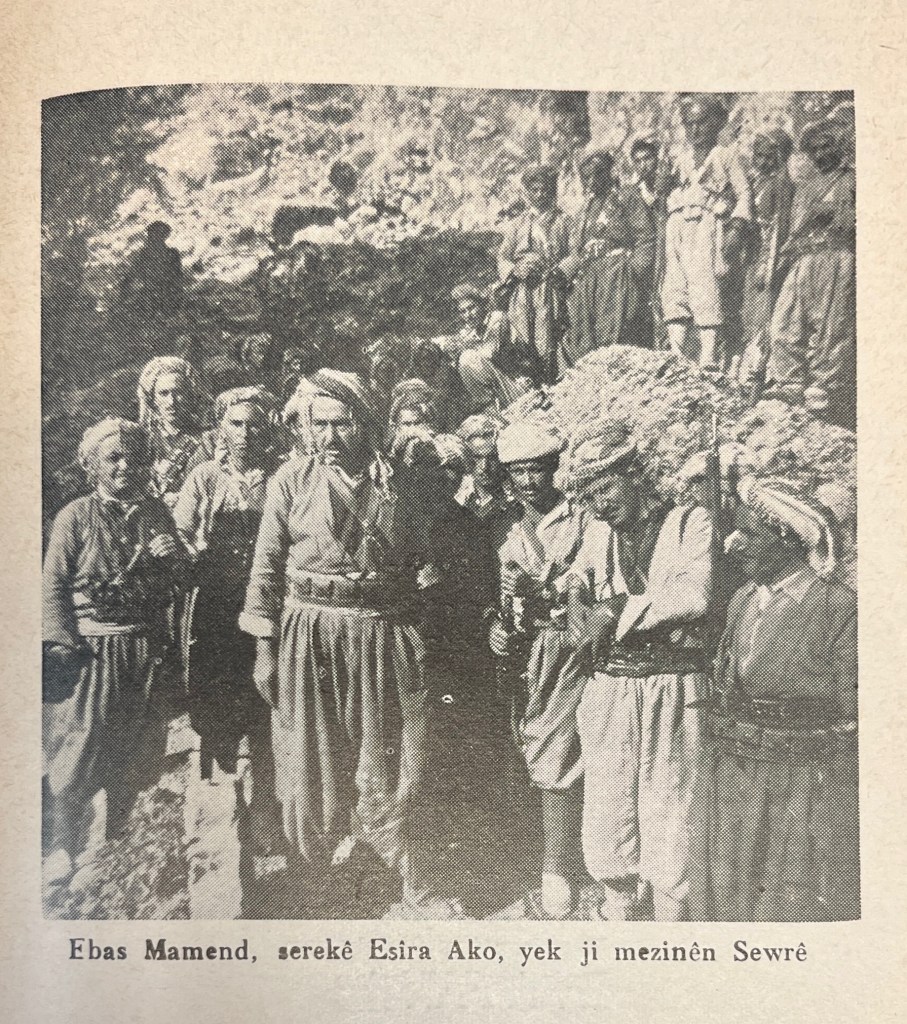

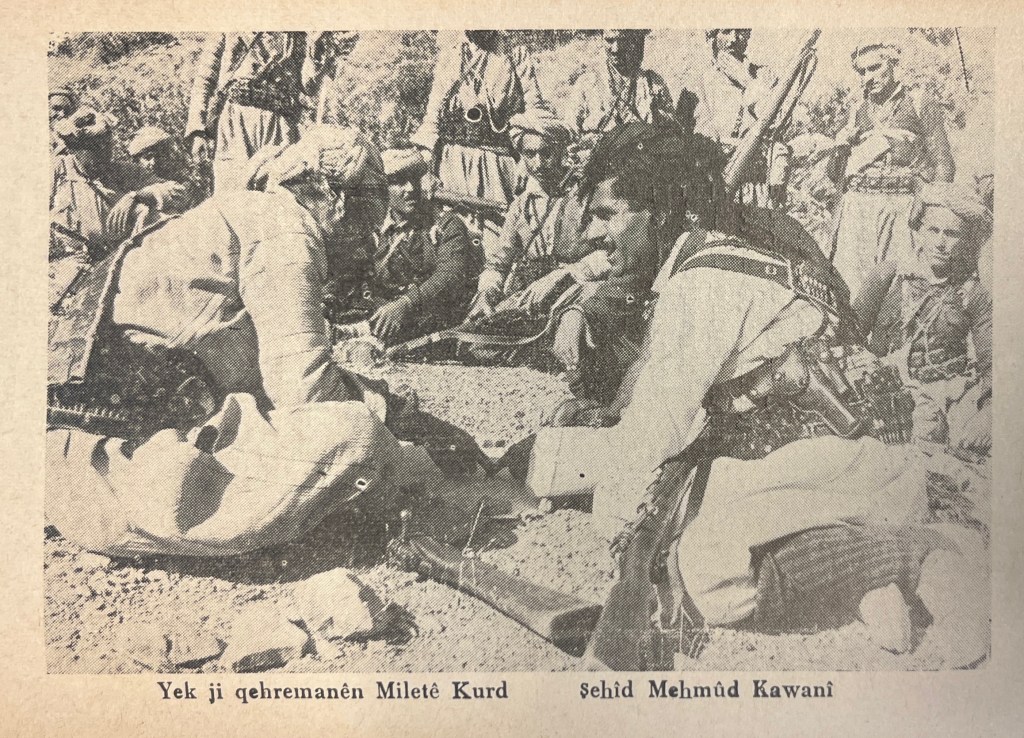

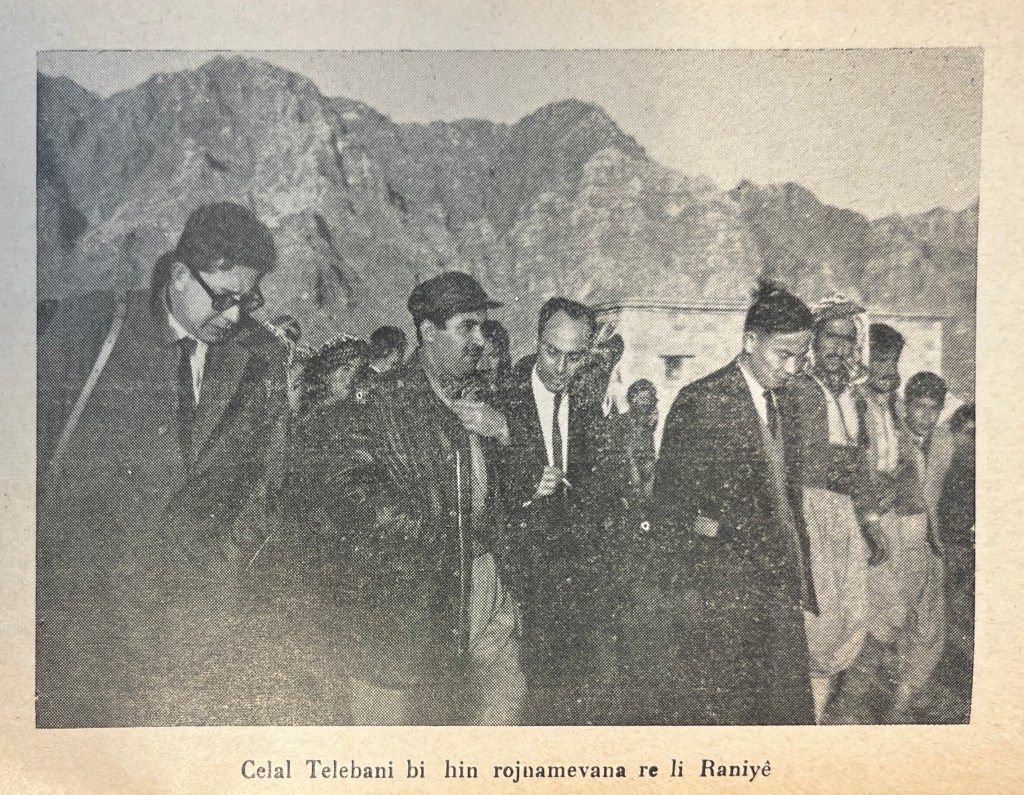

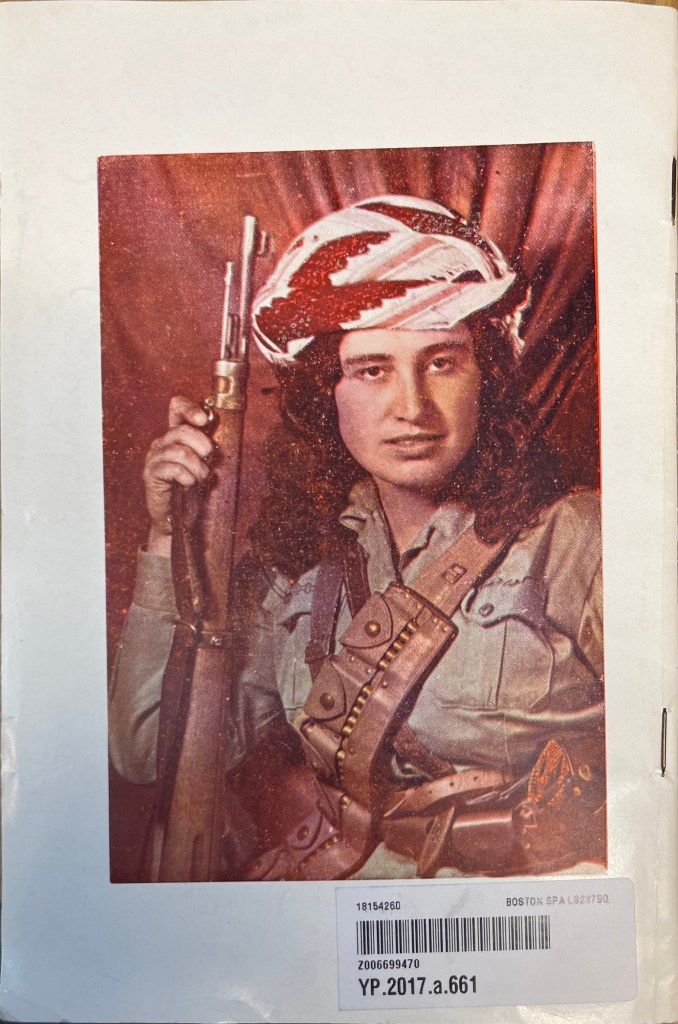

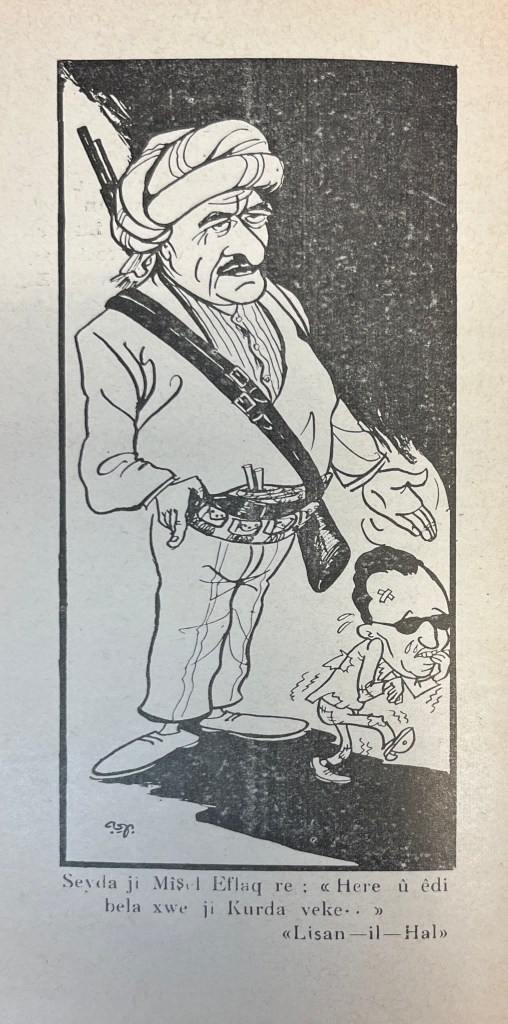

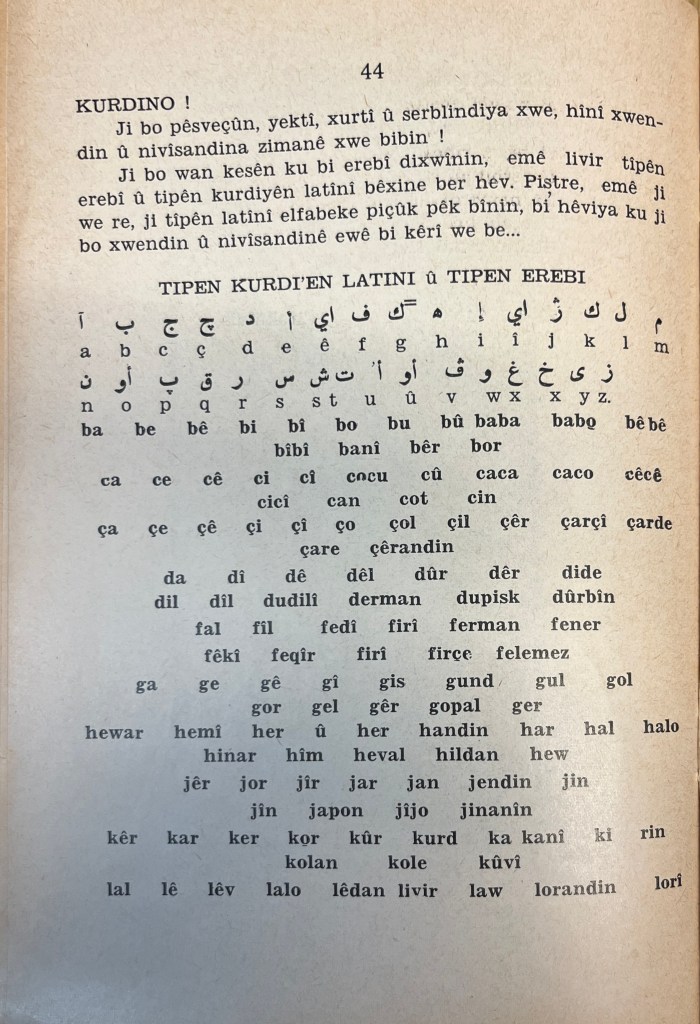

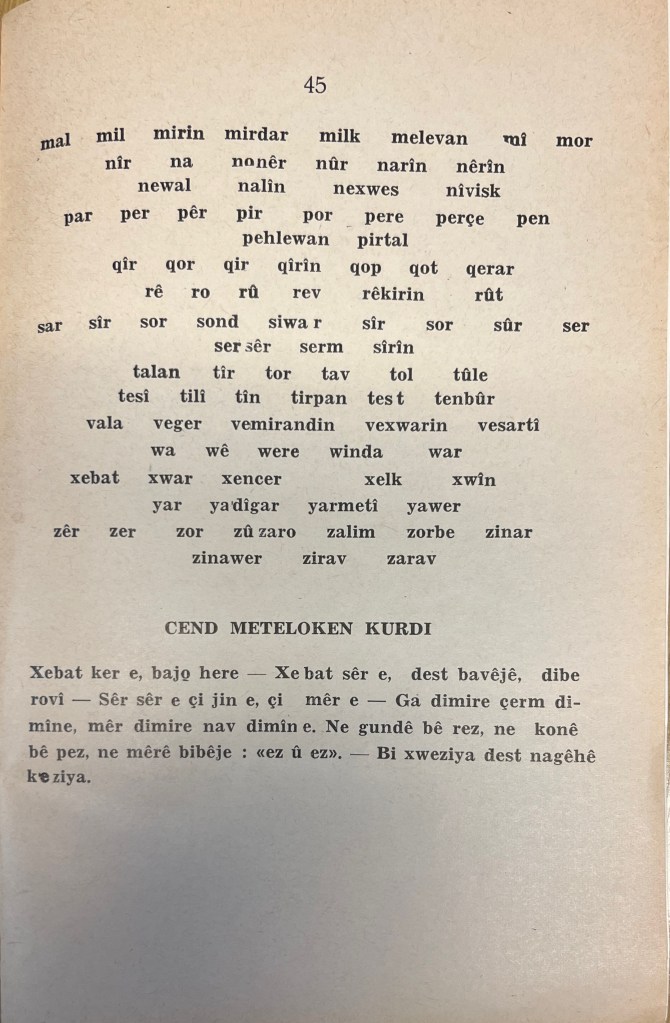

Comprised of 48 pages in total including an introductory letter by “Kurds outside of the homeland” (“Kurdên derveyê welêt”), the booklet is three patriotic poems of varying lengths, all dated, and a short explanation of the alphabet used. The three poems come from three different decades and authors: Berzanî: Serdarê Kurdistanê yê Bilind, 3 pages, by Q.C. (Qedrîcan) and dated 15 June 1947; Hatina Berzanî, four pages, by Rûgeş and dated 1958; and the eponymous Şerê Azadî, a whopping 27 pages, by Çiroknivîs (Story-writer), dated 23 June 1964. Among these literary works are photographs of Mistefa Barzanî, Celal Talebanî, PDK fighters in the field, various martyrs (Mahmûd Kawanî is named), a satirical cartoon of Michel ‘Aflaq, and, most striking of all, a colour portrait of Margaret George (Shello), “Jeanne D’Arc of the Kurds,” a famed Assyrian freedom fighter of the mid-20th century.

So far, so good – there’s really nothing about this publication that makes it particularly noteworthy, except, perhaps, its rich photographic content. All three poems make it clear that this is borderline propaganda for the Kurdistan Democratic Party (Partiya Demokrat a Kurdistanê). The PDK is a secular nationalist party founded by Mistefa Barzanî himself in Mahabad, Iran in 1946, where a short-lived Republic of Mahabad was declared on 1 January 1946. All three poems are laudatory of Barzanî, but they’re also a histories of the Kurdish struggle in the mid-20th century from the eyes of Kurdish literati. Here’s a taste of Qedrîcan’s call for a Kurdish-positive anti-colonial front across West Asia:

Ey biraderê Ecem!

Ixwan: Ereb-el-eşem!

Ey demoqrat Turk qardaş!

Birader… lxwan…. Yoldaş

Em, heval û cîranin;

Dujmin: Amerîkanin…

Ingilîz in, In.. gi.. lîz,

Zinhar, jê re, mebin lîz!

My highly unpoetic translation is:

Oh Ajami brother!

Ikhwān: Syrian Arab!

Oh Democratic Turkish brother!

Brother… sibling… Comrade

We’re friends and neighbours

The enemy: Americans

The English, En-gi-lish

Beware, don’t become their plaything!

Qedrîcan is well-documented as a poet, but pinning down the other two is less straightforward. Rûgeş is a mystery, as I have yet to find (online) mention of a poet by that bernavk or laqab. I suspect that he might be Mihemed Elî Heso, born in Mozan (is this related to Tell Mozan in northern Syria?) in the 1930s. A badly formatted collection of personal accounts and memories posted on Kurdîpedia relates that Heso published his first poem in 1956; that he was in Syria in the 1950s; that he knew Qedrîcan and other authors such as Nûredîn Zaza and Cemal Nebez; and, according to Zaza’s words, recited a poem about Barzanî called Hatina Barzanî in Damascus around this time. I think that this provides a good basis for my assumption.

The third poet, Çiroknivîs – an odd name for a poet – is a harder nut to crack. It is undoubtedly the more satisfying one, however, given that their poem is the staple of the publication. Şerê Azadî is, of course, the story of Kurds’ fight for autonomy, human rights and respect in the face of Great Power machinations, Baathist betrayals, and Arabist conspiracies in Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo. It’s completely in line with the two shorter poems that start the booklet, but its detail, scorn and vitriol also put it on a different level. Does this emotion betray something of its composer’s own life?

The magic of Google brought me to the answer. A search of a few lines revealed a possible link to an exiled, politically-active writer, Dr. Nûredîn Zaza. A Facebook post of mine embarrassingly spamming a few Kurdologists led the exceptionally productive scholar Dr. Angelika Pobedonostseva to direct me to Zaza’s fanpage on Facebook, where a 2019 post contained a confirmation that Çiroknivîs was indeed Nûredîn Zaza. The identification is handy, both for its ability to round out our view of Zaza’s oeuvre and for a broader understanding of the relationships between Kurdish poets in the 20th century.

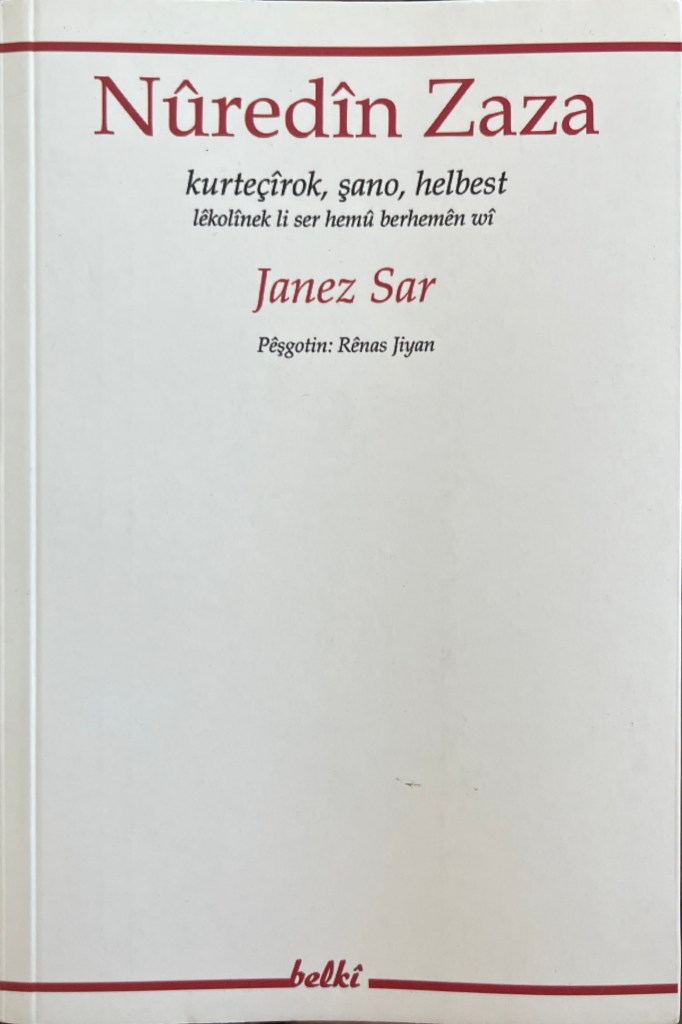

In his introduction to Janez Sar’s Nûredîn Zaza: Kurteçîrok, şano, helbest; lêkolînek li ser hemû berhemên wî (Nûredîn Zaza: Short stories, plays, poetry; a study on his complete works), Rênas Jiyan notes that Zaza, born in Maden near Elazığ, was forced into exile in Syria at a young age. In British-occupied Iraq, he soon became active in Kurdish political struggles and was forced to flee to Lebanon and Switzerland before returning to Syria and then Türkiye, suffering imprisonment in both countries. He eventually found refuge in France, where he was one of the founding members of the Institut kurde.

Zaza was also active as a literary critic and thought Qedrîcan a poet worthy of the fame of Nazım Hikmet or Louis Aragon – if only he had done something more than just write poetry. Zaza himself combined revolutionary Kurdish nationalist politics with a commitment to literary production over the course of his life. And, while Jiyan doesn’t always rate Zaza’s short stories as being of the highest literary calibre, he does point to the spectrum of patriotism, nostalgia, compassion and anger that create an arc of coherence across decades of Zaza’s writing.

So now we know that Şerê Azadî might be Zaza’s first attempt at weaving together his own political works with Qedrîcan’s poetry in a grand nationalist narrative. The impact on long-term Kurdish literary criticism was likely not quite what he had hoped for: Sar notes only three poems of Zaza’s that are significant from a political point of view: Derketî (an adaption of Lameneais l’Exlisé (?); 1941); Newrozeke Xemgîn (A Sad Newroz; 18 November 1978); and Newroza 1979 (19 February 1979). Şerê Azadî is not among those she views as being of significance for Zaza’s overall poetic development, or indeed for the employment of literature in service of Kurdish cultural and political emancipation.

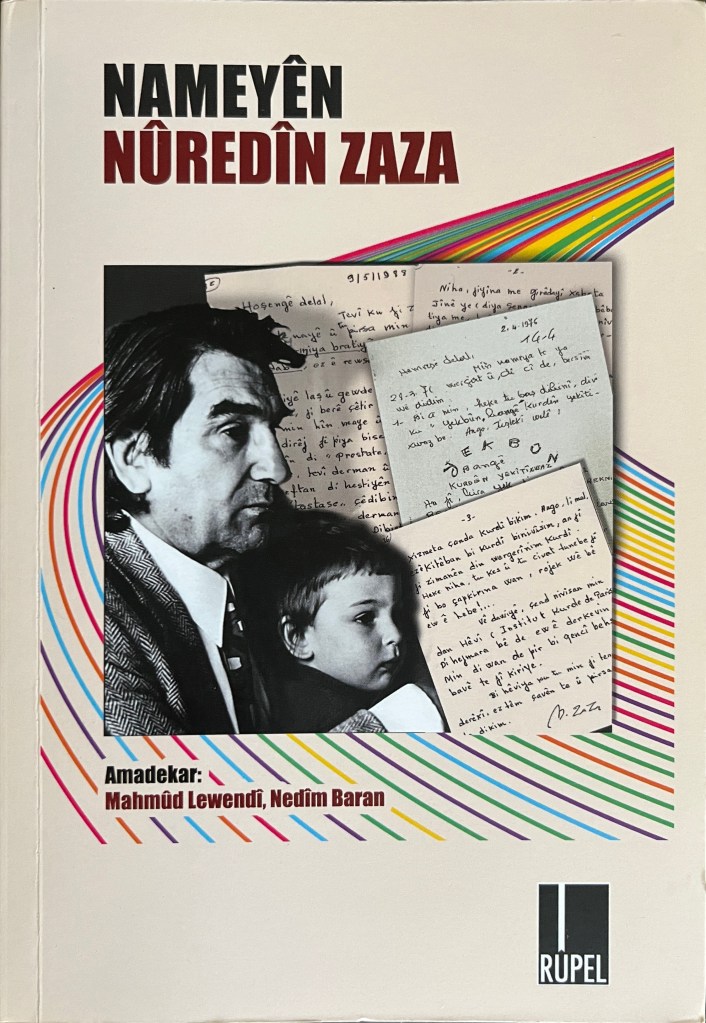

If Şerê Azadî failed to revolutionize readers, did it at least have some sort of special literary or political importance for Zaza? For the answer to this, we need to turn to Nameyên Nûredîn Zaza (Nûredîn Zaza’s Letters), edited by Mahmûd Lewendî and Nedîm Baran. The book is substantive – 273 pages in total, including index – and comprehensive, with photos of people and publications to provide greater context to Zaza’s epistolary relationships. It’s in this collection that we find a letter from Zaza to Hemreş Reşo dated 9 November 1964, likely written in Beirut, in which Zaza encourages Reşo to read and write more in Kurmancî as an act of political resistance. He also tells him “Ez niha hin ji ‘serpêhatîyên’ xwe dinivisîm. Lê, zû bi zû nikarim çap bikim. Me hîn pereyê ‘Şerê Azadî’yê dernexist” (“I’m now writing a few of my ‘experimental works.’ But I can’t print them quickly. We haven’t organized the funds for ‘Şerê Azadî’”).

Later in the letter, Zaza continues: “Kitêba min Şerê Azadî hate wergerandin [bo] erebî. Eger perê me hebe em ê wê jî bidine çapê” (“My book Şerê Azadî has been translated into Arabic. If we have the funds, we’ll have it printed”). I haven’t found a record of Zaza’s Arabic version published anywhere, but perhaps it’s still lurking in an archive somewhere in Beirut, or Damascus, or Lausanne, awaiting recovery by an eager scholar.

A second letter in the book, this time dated 12 January 1965 at Beirut, provides us with more information about Rûgeş and Zaza’s relationship to him. Zaza notes that the man (“ev mêrik”) has returned to Syria and been arrested there. He also remarks that changes made to Rûgeş’ “helbest-qesîde” (“poem-qasīdah”) meet the poet’s approval. Rûgeş apparently took a moral stance about the nature of his words: “Min hişt ku ew jî bawer bibe ku sixêf û dijûn ne bihayê ‘helbestekê’ bilintir, ne jî miletekî rizgar dikin. Em ê wan tiştan ji ‘iştirakîyên ereb’ re berdin” (“I heard that he believes that insults and swearing have no higher ‘poetic’ value, and that they don’t liberate a nation. We will leave those things [insults and swearing] to the ‘Arab socialists’; stress Zaza’s). Given the vitriol of Zaza’s own description of the Baathists and Arab nationalists in Şerê Azadî, this was evidently something that they had agreed to disagree about.

Finally, the same letter also helps us to narrow down where the booklet might have been published. In a further section, Zaza complains to Reşo about the problems of publishing in Kurmanci in Beirut:

“Çapkirina kitêboka min ez gelek westandim: Hin tîp peyda nabin (wek ş, ẍ û hin din) ên di kitêboka min de, ez bi dest wan rast dikim. Piştre, ji çapkirina pirtûkên kurdî re pir pere diçe; ji ya min re 800 LL [Lirê Lubnanê] çûn.”

“I’ve been worn down considerably by publishing my little book. Some letters that appear in my booklet can’t be found (like ş, ẍ and others), I have to sort them out myself. What’s more, a lot of money has been expended to publish Kurdish books; for mine, we’ve gone through 800 Lebanese lira.”

Indeed, both ş and ẍ are largely absent from Şerê Azadî, although ş does appear at times. This does seem to suggest that the work was overseen by Zaza himself in Beirut, a testament to Kurdish political activism in the country prior to the civil war and the difficulties around it. Zaza himself says that the government still stepped in to authorize publications; undoubtedly an attempt to control what could be a cause of soreness with neighbouring Syria.

In the end, however, Şerê Azadî remains a monument to the core role language and literature can and do play in the Kurdish political struggle. One small booklet, largely forgotten in the broader pantheon of Kurdish literary production, highlights the complexity of personalities, politics and practicalities underlying Kurmancî publishing over the 20th century.

I’ve largely avoided commenting on the works in the volume; perhaps an oddity for a post about a book of poetry. It’s my hope that the people involved will help to draw you in and act as a bridge to discover and enjoy this bit of Kurdish literary history for yourself.

Leave a comment