It’s been no small while since I last wrote. How I used to engage with this blog requires a bit of a memory jog. I haven’t been idle, not least thanks to my day job. But every now and then I’ve come back to From Altay to Yughur, yearning for the joys of free-form blogging.

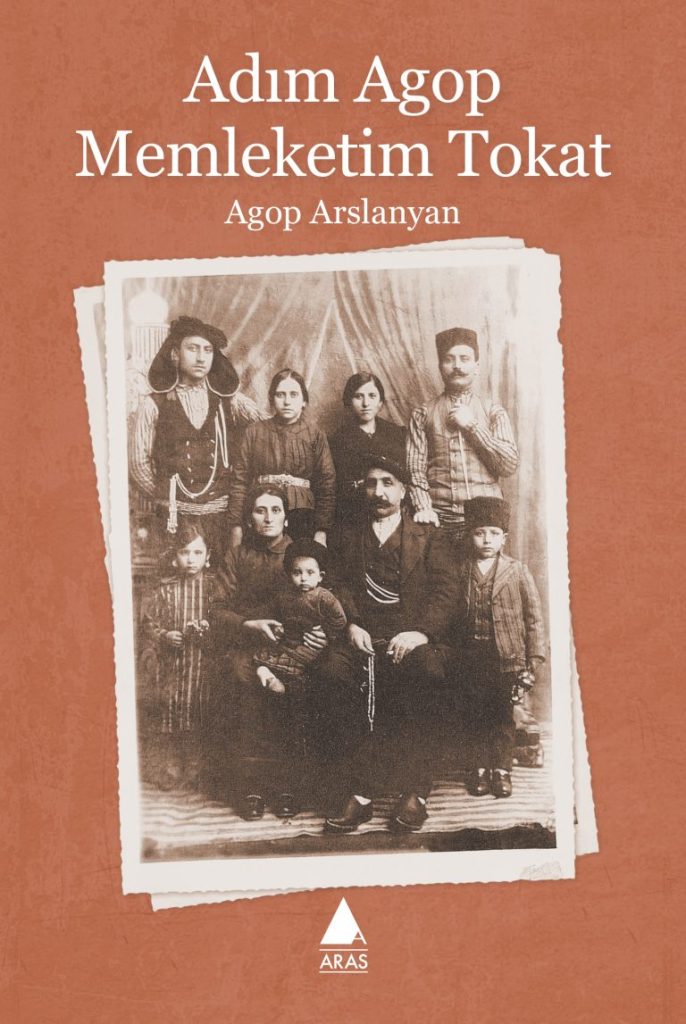

Memory is an apt starting point. I haven’t been taking it easy. On the contrary, I’ve been writing and reading loads, including memoirs. Among my most recent reads has been Agop Arslanyan’s Adım Agop Memleketim Tokat (My name is Agop and Tokat is my Hometown), published in 2005 by Aras Yayıncılık. The book is on its 7th edition (2022), which should give you some idea of its popularity.

Arslanyan was born in Tokat, which is close to Rize in Turkey’s Black Sea Region, in 1934. His youth was spent shuttling between Tokat and the village of Dodurga (Դոդուրղա), where his father worked as a miller during the summer months. In 1941, he witnessed his father’s conscription, along with everyone other non-Muslim adult man in the region, into the Turkish army, which dealt a debilitating blow to the family. In 1946, he made his way to Istanbul, first living with a cruel uncle and then with a kindly aunt. He remained in Istanbul, apprenticing to a jeweller and delving deep into Armenian literature and culture, learning the language only as a teenager. He married an Armenian woman he met through a youth group in 1963, and they remained in Istanbul until 1997, when he and his family migrated to Toronto, where he lived until he passed away in 2016.

Adım Agop Memleketim Tokat is a remarkable work because of Arslanyan’s framing. The work starts with a trip back to the town, where roads and houses and trees and parks all jog the author’s memories of people and events. These speak to the lives of the immediate post-Genocide generation of Anatolian Armenians. The return trip is by no means unique to Arslanyan: Vahram Burmayan, for example, recounted of his own visit back to Adapazar in an article originally published in Marmara in 1953 and republished in Հէ՜գ թուղթի կտորներ in 1999 by Aras. But Arslanyan’s factual travel is only a gateway into his virtual trip through memory and sentiment. The book quickly departs from disused churches and astonished Turkish neighbours to allow the author to paint a rich picture of his family and those people – Armenians, Kurds, Alevis, Jews, Rums, and of course Turks – whom he met along the way from rural Tokat to the concrete of Istanbul.

Adım Agop sticks out because of the humanity with which Arslanyan imbues all characters in his account. Apart from his mother and father – whom, for obvious reasons, the author depicts as admirable, loving, and very considerate people – all individuals come to us as humanly as possible. He does not shy away from the brutality of Turkish officers or Kurdish agas visited upon Armenian villagers. But neither does Arslanyan gloss over the anger, cruelty or miserliness of an Armenian farmer towards the rebellious horse he’s gifted; the anti-Semitism of Tokat’s Christian and Muslim children; or the blind anti-Kurdish and anti-Roma sentiments of an Alevi elder. Together with an uncaring and cheap uncle; a capricious but shrewd future wife; and a compassionate Turkish officer willing to let Agop’s father say goodbye to him before being drafted into military service, the portrait that he paints is of an Anatolia filled with real people, buffeted by real passions and emotions, denying the hard, unforgiving stereotypes of later creations.

Arslanyan’s memoir left a deep impression on me because of its candour and honesty. But also because of how it compared to some of the other works that I’ve read recently. It’s hard to compare his work to some of the better-known Genocide survivors’ stories – including I Ask You, Ladies and Gentlemen by Leon Z. Surmelian (thanks for the recommendation, Vazken Davidian!) – because Arslanyan did not experience the Genocide himself. His is an experience of rebuilding and adaptation to the Turkish nation-state, rather than survival and recovery.

In my limited experience, the closest to Adım Agop is Tanrı’ya Adanmış bir Yaşam by the former Patriarchal Exarch of the Syriac Catholic Church in Turkey, Father Yusuf Sağ. Sağ is a native of Azekh/Bazabday/Hezêx/İdil, which I described in an earlier blog. Arslanyan’s work is concerned with providing a sensorial, affective history of post-Genocide Tokat and its Armenians. Sağ’s approach is much more factual – as factual as any memoir can be – and chronical-like in its accounting of time and space. He starts with a brief explanation of the history and culture of Azekh before proceeding to a reckoning of his life from childhood to his late 70s. The stories here are interesting, and at times a bit repetitive, but by and large the picture that emerges is one of a single, very determined man’s accomplishments across multiple countries and organizations.

Sağ’s story takes place in various locations – southern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Istanbul, Germany and Sweden, with a few stops in Rome as well. His narrative tells us much about the nature of Syriac Christian communities in Turkey and across the Middle East, and about the workings of the Syriac Catholic (Maronite) and Syriac Orthodox Churches. As such, there isn’t much about inter-ethnic relations, or, for that matter, about inter-personal relationships. As a priest, he deals with the emotions and actions of those around him with a level of forgiveness and understanding that we might not expect of a layperson like Arslanyan. Nonetheless, we do intuit the difficulties of co-existence in Anatolia, of Sağ’s struggle to encourage mutual understanding and acceptance, particularly in the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

Sağ’s position within the community and in quasi-official structures in Turkey (the Syriac Catholic Church was not recognized formally by the Turkish government through most of his career) creates its own barriers to the author’s candidness. But in between his politely veiled approaches to discord, we get a sense of the political, social and economic divisions that crisscross the region and its peoples. This is intensely personal at times, especially when it comes to Sağ’s conversion from Orthodoxy to Catholicism. Other examples come with the tinge of regret or rancour, as with his political aspirations, and his perceived support for the Demokrat Partisi and its successors. But, through and through, Sağ demonstrates how lived proximity has not translated into an environment of accepting co-existence and cooperation, especially when it comes to access to economic resources.

Is this really all that novel? Given the history of inter-ethnic conflict in Anatolia, and across the former Ottoman Empire as a whole, this focus on the lived experience of tension and interpersonal strain might seem like yesterday’s news. But I come back to it to nuance rosier pictures of Anatolia’s history. A lot has been produced in recent years about the wonders of the region’s multiethnic, multilingual, multi-faith tapestry, often from the viewpoint of the (Turkish-dominated) state or the now regionally-dominant Kurdophone communities. These narratives don’t necessarily deny a past fraught by violence or discord, but they do present a picture ripe for re-use, a parable that utilizes a folkloristic past for a tolerant future.

The book that I’m thinking of most clearly is Kemal Varol’s Ucunda Ölüm Var, published in 2019. Varol is a Diyarbakır-born Turcophone poet of Kurdish origin who has now authored six novels. Ucunda Ölüm Var is the story of an elderly woman who earns her way by singing dirges at funerals (ağıt yakmak), helping to release the pain and trauma of loss. Ever on the hunt for her own love, a prodigious musician and dengbêj, she travels across Eastern and Southern Anatolia, signing dirges and mourning the rupture of the region’s multiple ethno-religious communities. The narrative is melodramatic but poignant, and Varol highlights the diversity of the peoples who live on this land. The protagonist is herself lost, but with the help of those whose stories she hears and whose pain she releases, she too realizes catharsis. In one sense, Varol’s work looks to show that recognition and reconciliation across multiple fault-lines and divisions is the only way to achieve collective healing.

Such narratives are uplifting and inspiring. The problem is their failure to revolve around the experiences of those who have lost the most and for whom the benefits of reconciliation are far from certain. They are predicated on the paths dominant groups map. Such routes therefore encapsulate memories and roles most convenient for dominant storytellers, rather than the marginalized.

I’m certain some minoritized voices do spell out such painful and complicated memories on the contemporary Türkiyeli literary scene. I’m not versed enough to list them off the top of my head. But two novels produced in exile do speak to these themes. One is Hamastegh’s The White Horseman (Սպիտակ Ձիաւորը), a US-published novel of epic flavour (but not length) about an Armenian youth/titan who challenges Kurdish-Turkish tyranny in Eastern Anatolia. The young man both liberates his people from the threat of annihilation and rescues his beloved, a young Kurdish woman (who, spoiler alert, is likely of Armenian origin). Hamastegh’s novel was written between the early 1930s and 1952 and is therefore far closer to the horrors of the Genocide (which Hamastegh did not witness first-hand) than Arslanyan’s memoir. The author (whose real name was Hampartsum Gelenyan) was born in Harput, near Elazığ in East-Central Anatolia. Even if his narration is not intended to provide the same level of description of reality that we see in Adım Agop, it nonetheless paints a far less tolerant picture than depicted by Ucunda Ölüm Var. Certainly, the answer of the White Cavalier is not that catharsis leads to productive inter-communal dialogue, but rather that autonomy and self-defense are the only routes of self-preservation.

While not a Genocide-survivor in the strictest sense, Hamastegh grew up in an environment informed by the bloody upheavals of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His is therefore a memory of the time before the nation-state, formulated in the period of the nation-state. A better comparison in terms of chronology is Thōmas Korovinēs (Θωμας Κοροβινης), whose novella Fachise Tsika (Φαχισε Τσικα) tells the story of a fictitious Pontic Greek woman who makes her way to Istanbul, where she ends up employed as a sex worker. Korovinēs’ portrayals can, at times, be very broad brushstrokes and some characters verge on stereotypical. But the short work is an interesting approach to post-Exchange Greek life in Turkey, making ample use of first-person narration to include Pontic and Turkish expressions. The story, which is pretty simple, is dotted by interactions with peoples of all different ethnicities, religions, nationalities and social classes, providing a colourful but multilayered glimpse into mid-20th century Istanbulite life. Fachise (a Hellenized version of the Turkish slur for a sex-worker) is candid in her appraisals, and equally damning and welcoming of both Greeks and Turks. Korovinēs admits that her words are a mixture of the real and the imaginary, a dramatization of actual experiences. In massaging them to fit the narrative, he provides a taster of what life became, without much moralizing about what it should be.

This is the beauty of many of both Arslanyan and Korovinēs’ works. Memory is a crucial part of healing, but nostalgia can be a dangerous drug. It’s easy to imagine golden pasts or cruel wastelands of time. But in doing so, the characters in these stories – real or imagined – lose their humanity, and with it their power to inform the present. Agop and Fachise, as warts-and-all portraits, remind us that healing is hard because of our own complicated natures, as well as those of the individuals around us. Nothing could be a better antidote to the homogenizing steamroller of chauvinistic nationalism, whether of the dominant or the dominated.

Leave a comment