This blog is tied to the Britanahay Բրիտանահայ: Armenian and British display at the British Library, produced in collaboration with the Armenian Institute.

As part of the Britanahay Բրիտանահայ : Armenian and British display in the British Library’s Sir John S. Riblatt Treasures Gallery, we focus on Armenian communities in several countries formerly subject to British colonization. Among them is Cyprus, occupied by British forces in 1878 and formally part of the Empire from 1914 until 1960, when the island won its independence after a protracted struggle against British domination. Cyprus is often portrayed as suffering from a two-sided dispute between Greeks and Turks, sometimes referred to as “the Cyprus problem.”

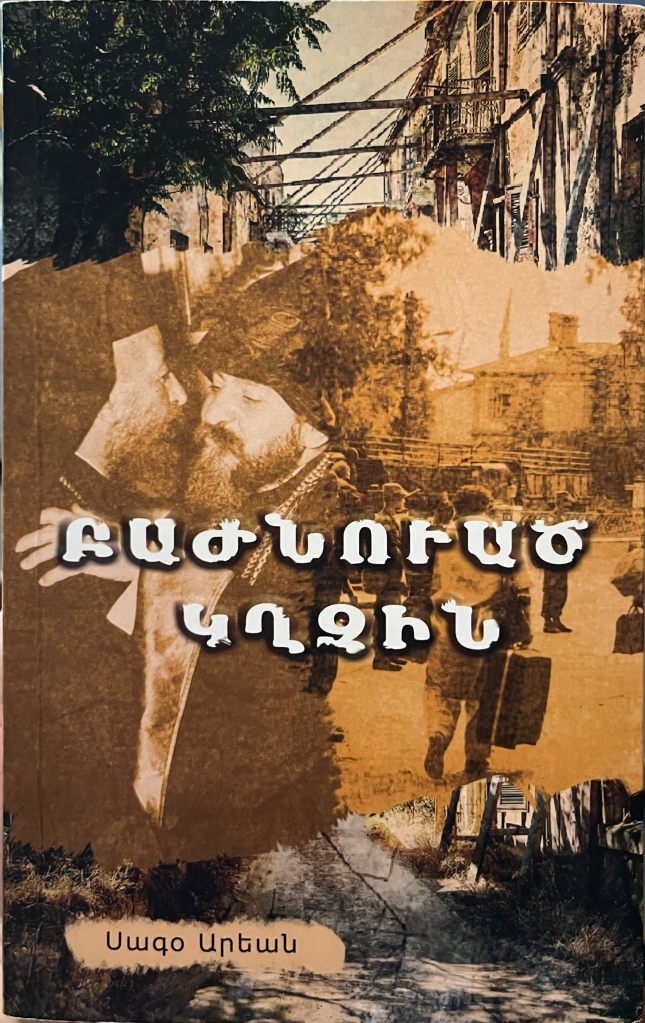

But in addition to the dominant Greek- and Turkish-speaking communities, the island has also long been home to Armenians, Arabic-speaking Maronites, Afro-Cypriots, and Jews. Their voices are frequently absent from international media, which prefer to see this as a problem of halves (conveniently also leaving out British and American interventions). Local activists, however, continue to fight such erasure. Indeed, a brief look at the online magazine Gibrahayer, founded in 1999, shows the vibrancy of such efforts. In 2024, Sako Aryan’s Բաժնուած կղզին (Divided Island) gathered the testimonies of some 25 Gibrahayer (Cypriot-Armenians) to mark 50 years since two closely-linked pivotal events: the 1974 coup d’état by Greek nationalists, which toppled the elected President Archbishop Makarios III; and the Turkish invasion and occupation of the northern half of the island, resulting in the declaration of independence by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in 1983. The book provides an invaluable resource for anyone interested in modern Cypriot history from the point of view of one of the country’s minorities. Many of the accounts flit between Cyprus-wide impacts of division and occupation to those specific to the Armenian community. They highlight the challenges of dispossession, dispersal and cultural retention for a group whose language is not official and whose presence on the island is not guaranteed by a more powerful foreign state. Armenians qualify as a “religious group” under Article 2 Paragraph 3 of the 1960 Constitution, which enshrines communal rights, but not to the level of the Greek and Turkish Communities formally mentioned in the document.

Aryan’s work (reviewed in Western Armenian by Rupen Janbazean for the Istanbul-based Agos) has a heavy emphasis on late 20th-century history. This is largely because it gathers the testimony of living Gibrahayer. The British Library’s Britanahay display helps to point us to an earlier pre-Independence existence, one that reflects even more strongly the impact of British colonialism on the island and the community. Visitors to the Treasures Gallery are confronted with two examples of Gibrahay life. The earlier one, Մայրերու գիրքը (Mothers’ Book), is a 1933 translation of an English manual for new mothers authored by L. Shepherd. I haven’t been able to identify the original author of the work. The volume does demonstrate the profound influence that British culture, education and morality had on Armenians now resident in a British Crown colony. Many of Aryan’s interviewees, as well as the contributors to the Armenian Institute’s Heritage of Displacement project, speak of such impacts. You can hear some of their stories in Cyprus-focused excerpts on the Institute’s website.

Education is key topic because of the role played by the island in Eastern Mediterranean history. The focus on Cyprus, as well as Egypt, allows Britanahay to explore the issue of anti-Armenian violence through a different lens. From the Hamidian massacres of the 1890s onwards, this British-controlled territory provided Ottoman Armenians with a safe haven. The voyage was not without its perils. As Reverand Krikor Behesnilian wrote in Armenian Bondage & Carnage, published in 1903, “Some of my countrymen, who had engaged boatmen to take them to Cyprus, were thrown into the sea during the passage.” If they made it to Cyprus, Ottoman Armenians could breathe a sigh of relief, as did Krikor’s wife Semagule, quoted in the same book: “We arrived at Cyprus at last, and the anxious husband and father, wife and children met again under the British flag.” Some, like the Behesnilians, would continue onto England. Others would stay in Cyprus, where they would start anew. As some interviewees in Aryan’s book explain, many settled close to Turkish neighbours, as they had a common language (Turkish) and some shared customs, allowing for life to resume without a complete cut with the past. Such patterns would have profound impacts on the course of mid-20th century Cypriot-Armenian history, when division and physical separation were presented as the most suitable solutions to Greco-Turkish disputes.

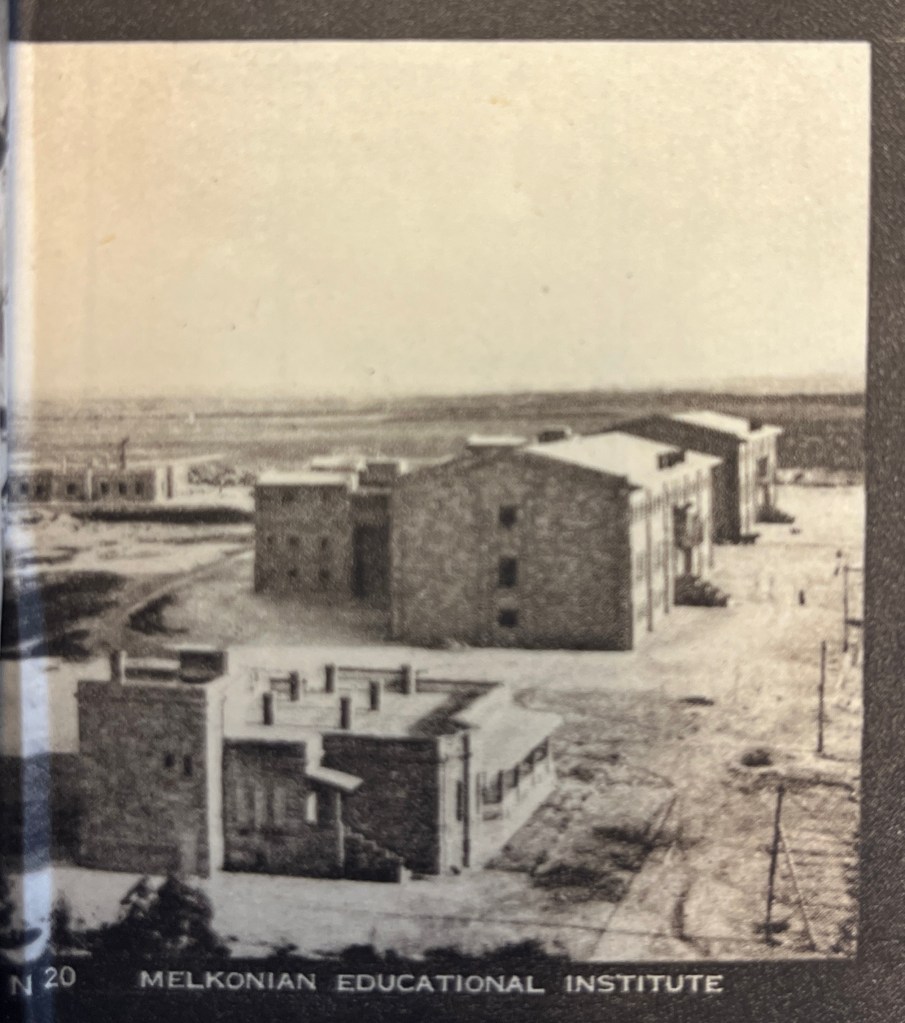

Among the bedrock institutions of this burgeoning Gibrahay presence was the Melkonian Educational Institute, which opened its doors in 1926 as the island’s largest Armenian-focused educational institution. Throughout the 20th century, the Institute provided a sanctuary for Armenian children – orphans of the Genocide or otherwise – to grow and blossom. It hosted students from across the Diaspora and, despite suffering bombardment during the 1974 Invasion (luckily during a break, when no students were in residence), it continued operations until 2005.

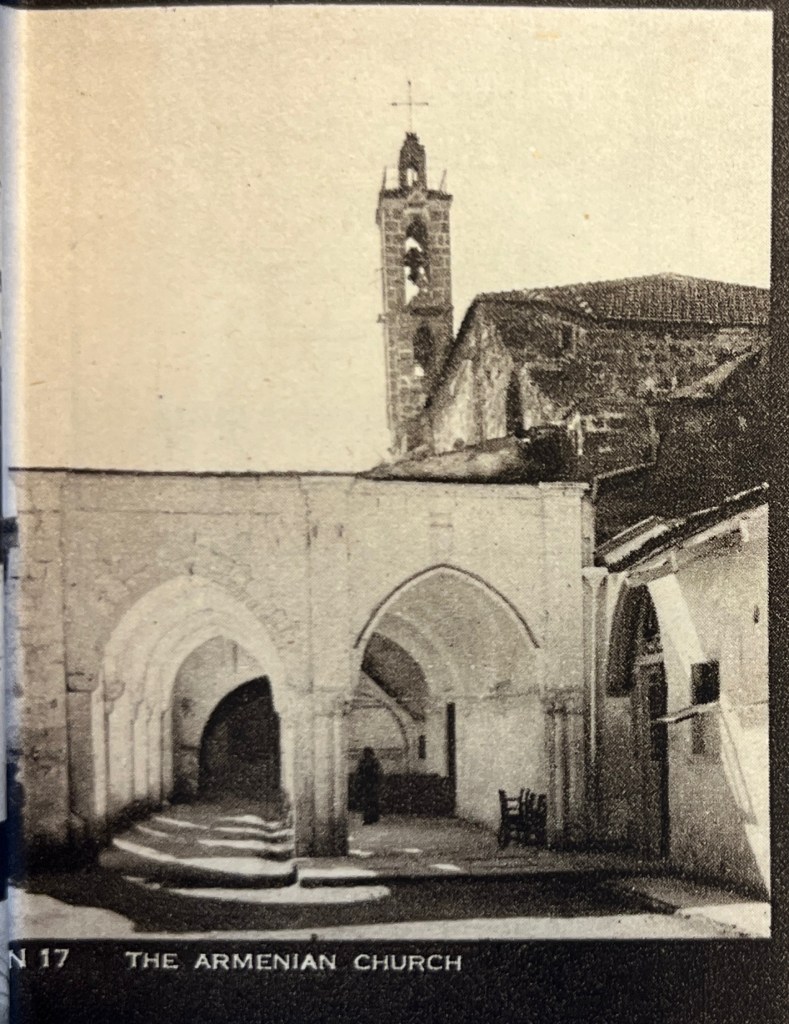

A photo of the Institute is on display as part of the second Cypriot work in the exhibition, The Island of Cyprus, compiled by the Mangoian Brothers and published in London in 1947. I’m very much indebted to Holly Kunst of the Centre of Visual Arts and Research in Nicosia, Cyprus for putting me onto Mangoian Bros. Studio, opened by Haig and Levon Mangoian in 1924, and especially the work of Haigaz Mangoian. The Island was intended for as broad an audience as possible. It’s clear that the Mangoian Brothers, with their inclusion of images of the Melkonian Educational Institute and the Surp Astvadzadzin Church in Nicosia, were aiming to encourage the view that Cypriot history and identity were imbricated, a mosaic of the country’s multiethnic, multifaith and multilingual past and present.

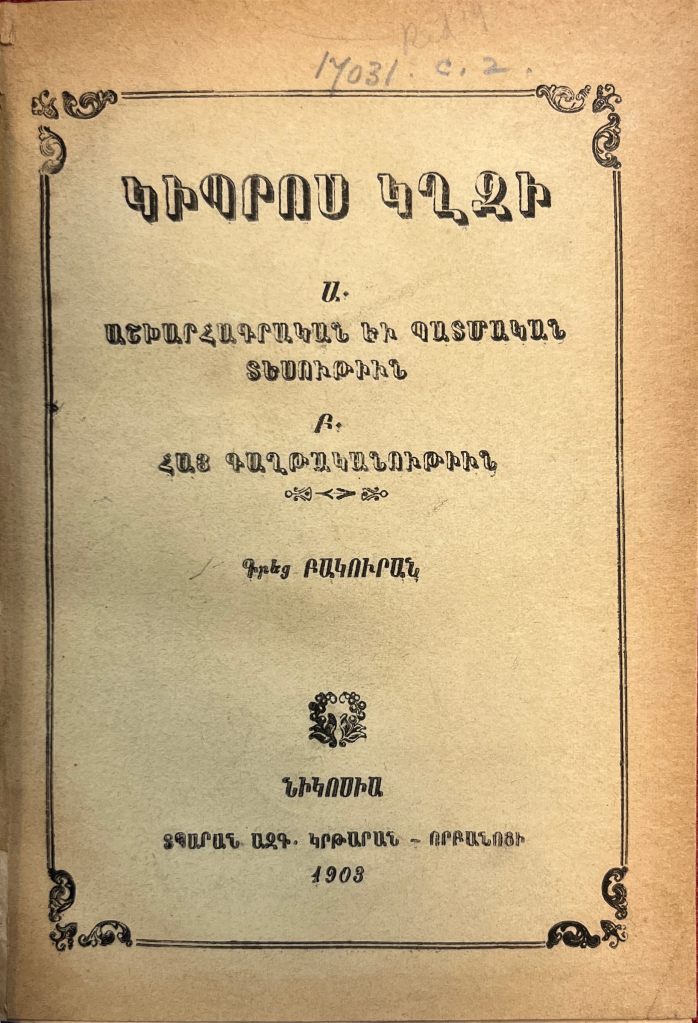

Their work shares its name, at least in translation, with another earlier book published in Nicosia. The Western Armenian Կիպրոս կղզի (The Island of Cyprus), written by Bakuran (Paguran in Western Armenian), was published by the National Gymnasium-Orphanage (Ազգային Կրթարան-Որբանոց) in Nicosia in 1903. This volume is comprised of two parts, the first a geography and history of the island and the second a history of Armenian settlements (Part 2). The book mixes extracts of Grabar manuscripts about Cypriot Armenians with the author’s own analysis of historical evidence of Armenian settlements. Although citations are far from perfect (or present, in some cases), Bakuran traces the first documented Armenian presence on the island to 868 CE, when the Byzantine Emperor Basil I sent an Armenian soldier, Alexis, to Cyprus in a failed attempt to restore Byzantine rule over the island. The narrative continues up to the contemporary moment (that is, the first years of the 20th century), establishing, effectively, a communal history for Gibrahayer that is Armenian-focused.

Bakuran included a special mention for about the establishment of the current building of the “Armenian Church,” our Surp Astvadzadzin mentioned above, which was rebuilt in 1308-10 following an earthquake. Although not originally an Armenian church, it was formally handed over to the Apostolic Church by the Ottoman authorities in the late 16th century. This chapter of Կիպրոս Կղզի highlights the importance of the institution, while also reminding us (unintentionally, of course) of the pain that its seizure in 1963-64 must have induced across the community.

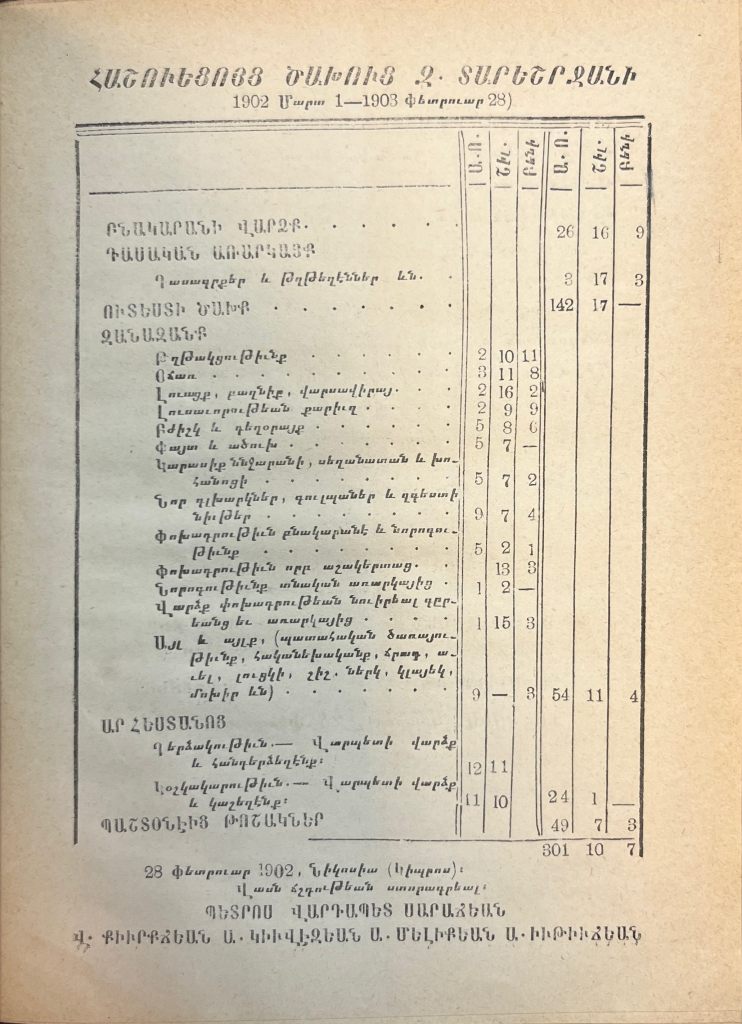

The publisher of the volume, the National Gymnasium and Orphanage, opens another productive vein of investigation. Bakuran’s second volume, Մի տեսութիւն Կիլիկիոյ հայկական իշխանութեան վրայ (A Look at Cilicia’s Armenian Principality), was published by the same outfit 1904. I have found three other publications from the same publisher: a memory-book in honour of the 1900th anniversary of Holy Echmiadzin; Տնական Դաստիարակութիւն (Household Education), translated from the English and published in 1903; and four accounts books for the institution itself. The volume in the British Library’s holdings is entitled Ազգային կրթարան-որբանոց ի Կիպրոս: Տեղեկագիր: Զ-տարեշրջանի: 1902 Մարտ 1-1903 Փետրուար 28 (The National Gymnasium-Orphanage of Cyprus: Statement: 6th Annual Cycle 1902 March 1 – 1903 February 28), this latter work highlights yet another aspect of the Armenian presence in Cyprus during the Cyprus Convention period.

The book is a brief look at the running of an essential institution for Armenian cultural preservation through some of the nation’s darkest years. It provides us with a sobering view on the sacrifices and commitments made by Gibrahayer in service of their community’s continuity. Of the more than £301 expended on the running of the school and orphanage, nearly half (£142 17s.) were spent on foodwere spent on food for those studying or living at these facilities. The funds to cover such expenditures were raised locally as well as in the Diaspora. It’s clear from the patrons and management of the Gymnasium and Orphanage that this was an effort that united Gibrahayer with Armenians in Manchester and London, as well as France and the US.

The maintenance of historical narratives and spiritual sustenance are, without doubt, key elements in the preservation of an identity. But Cyprus’ frontline position as an initial stop for those fleeing persecution and the Genocide also implied sustaining the frail, the vulnerable, and the unprotected. The will to survival and renewal was clearly strong amongst those supporters of the Gymnasium and Orphanage at the turn of the century, just as it comes through in the accounts collated by Aryan in Բաժնուած կղզին. It is an ethos that I hope comes through to those who visit our display, where they have the opportunity to contemplate the place of Gibrahay cultural production among the broader heritage of Britanahayer.

Britanahay Բրիտանահայ: Armenian and British is open 7 days a week in the John S. Ritblatt Treasures Gallery of the British Library until 22 February 2026. It was generously supported by the Armenian Institute and the Benlian Trust. I would also like to thank Senem Gökel for her immense assistance in connected me to sources on the history of Cypriot Armenians in Cypriot memory institutions.

Leave a comment