Since opening on 27 September, Britanahay Բրիտանահայ: Armenian and British has enabled me to connect with the Armenian community in London and Armenians around the world. Together with the Armenian Institute and their groundbreaking Heritage of Displacement project, we’ve had the chance to dig out materials about community organizations, events and disputes to emphasize the richness and diversity of Armenian communities in the United Kingdom. But the HOD recordings included in the display remind us that communities are made of individuals, each of whom has their own story to tell. In this blog, I want to move away from grand, sweeping overviews to focus on the singular. Here, I’ll aim to provide a look at some of the personalities featured in the display, teasing out bits of information that didn’t fit on the labels.

In the display, the third book from the left is a small volume entitled In Bonds: An Armenian’s Experience. Published in 1896 by Morgan and Scott, it is Reverend Krikor Behesnilian’s account of the everyday existence of Anatolian Armenians in the late 19th century, and the violence visited upon them during the Hamidian Massacres. From the work itself, we glean a bit more information about Behesnilian. The title page of In Bonds identifies him as the author of No Mean City, but the only other publication I’ve been able to find him associated with is Armenian Bondage and Carnage: being the Story of Christian Martyrdom in Modern Times. A catalogue search for Behesnilian reveals that his wife, Semagule, wrote Armenia in the Time of the Massacre: By a Lady Survivor, published in 1915.

Krikor was born into a family of Armenian Protestants in 1859. He began preaching on behalf of the American Mission in 1885, successfully converting several members of the Armenian Evangelical Church. In 1888, he came to the UK to further his theological studies and “make Christians in England acquainted with my country and work,” according to the text of In Bonds. He studied at New College in South Hampstead, eventually founding the Tarsus Bible-Teaching Mission in 1892 with local financial support. Later that year, he was ordained in Tottenham and returned to the Ottoman Empire to continue his missionary work. He met and married his wife Semagule the following year. As she was also from a Protestant family (the daughter of an interpreter for the American Mission), they were married “mainly in English fashion”… “attired in English costume.” Behesnilian remained in the Ottoman Empire (which he refers to as Cilicia) until 1895. His 1896 account relates his proselytization of local Armenians. But it also details Ottoman authorities’ increasingly aggressive attempts to block his travels based on his communication with British royals and politicians (including William Ewart Gladstone) and his spread of British influence among Protestants in the region.

He evidently returned to Anatolia, likely with the financial assistance raised through In Bonds. He was able to stay there till 1899, when, according to the introduction to Armenian Bondage and Carnage, “my family who survived the massacres, had to fly the country, their lives being in danger, and, in the year 1901, my only brother escaped also. We are now exiles…” There is a clear shift in this 1903 publication that demonstrates a weakening of British interest in Armenians’ conditions in the Ottoman Empire. It also documents the watered-down protection offered by British citizenship: “I ascertained from the Home Secretary that my naturalization would not protect me, for in the Sultan’s opinion that counts for nothing.” Mrs. Behesnilian and the Behesnilian children only found safety through their escape to Cyprus, then under British control, while Krikor’s father-in-law was protected through American intervention. Indeed, much of the book is taken up with calls for Britain to remember its commitments to the Ottoman Armenians and to intervene on their behalf as it once intervened in Macedonia.

At the start of the First World War, Behesnilian apparently wrote to Sir Edward Grey, then British Foreign Secretary, encouraging him to view Anatolian Armenians as natural allies in the battle against the Ottoman Empire (Foreign Office archival paper FO 371/2130/9911). The trail goes cold largely after these materials. Articles (behind paywalls) from various newspapers in Vermont and Wisconsin indicate that Rev. Behesnilian lectured across the United States following the First World War. From genealogical data on Ancestry.com, he died in Hennepin County, Minnesota, USA on 24 November 1924, with Semagule surviving him till 1938. Despite their strong attachments to English customs, both apparently decided to leave the UK for greener pastures in the US.

Just beside Behesnilian’s book is Armenian Legends and Poems, a 1916 publication by Zabelle Boyajian. Unlike the erstwhile Reverand, Boyajian is far from a mystery. She has her own Wikipedia entry in 13 languages and a detailed entry on the website of the Centre for Armenian Information and Advice. A thorough description of her life and accomplishments in Western Armenian by Anush Truants, meanwhile, can be found on Jamanak’s website. Boyajian’s work speaks for itself, but a bit of additional information wouldn’t hurt. Born in Diyarbakir in 1873, the child of British consul Thomas Boyajian and Catherine Rogers, she left for the UK after her father’s murder during the Hamidian Massacres. While in London, she studied art at UCL’s Slade School of Fine Art.

Part of the problem with exhibitions is that we can only exhibit one opening of a book, and this obscures the richness of an item as well as its creator’s broader oeuvre. This is certainly the case with Boyajian’s Armenian Legends and Poems, where a different opening would have highlighted her love for the work of Raffi, the greatest Armenian novelist of the 19th century, as well as her deep relationship with the whole Raffi family. Over the years following the publication of Armenian Legends and Poems, Boyajian worked tireless to promote Armenian culture and causes among non-Armenians in the UK while also exhibiting as an artist across the UK, Europe and Egypt. She passed away in London in 1957 and is buried at the Surp Sarkis Church in Kensington.

The section that follows Boyajian’s masterpiece places us firmly in the latter part of the 20th century. Here, we meet individuals who made a considerable impact on post-War Armenian-British life as well as British relations with the Diaspora and the (Soviet Socialist) Republic of Armenia. First among them is Haig Caro Galustian (Հայգ Կարօ Գալուստեան), an Iranian-Armenian businessman and philanthropist who was one of the publishers of Aregak (Արեգակ) in the 1960s and 70s. There is considerably less out there about Galustian than Boyajian, but more than Behesnilian. A 1960 photographic portrait of the man in the National Portrait Gallery (above) gives you an indication of his presence and importance. A brief comment from 2018 left by his daughter Tatiana Galustian shows the love and affection felt for him by his family. But his obituary from The Times provides a fuller picture of his life story. Born on 21 December 1907 in Iran, he played football for the Iranian national team in the 1930s. During the Second World War, Galustian made successful inroads with British troops occupying the country, building up business acumen and contacts (as well as wealth) as the liaison officer for the UK Commercial Corporation. He ensured “an even distribution of commodities, such as wheat and kerosene, throughout the British zone of occupation in southern and eastern Iran” (according to the obituary). His links to Britain and appreciation for its culture deepened. They eventually lead to a Anglophilic attitude so pronounced that the later-deposed (by the British) Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq expelled him from the country in 1951, claiming “he had drunk too deeply from the Thames water.”

Galustian evidently retained contacts and contracts in Iran after the 1953 coup that toppled Mosaddeq. The 1954 publication The Marconi Companies and their People notes that he was their representative in the country at that point. The same can be said of Beagle, a British aeronautics firm. He eventually settled in Wimbledon, becoming prominent among local Armenians but also the wider community. In 1959, he endowed a garden behind St. Mark’s of Wimbledon in memory of his mother. Throughout the 60s and 70s, Galustian would further develop his role binding Iran, Britain and Armenia through commercial and cultural ties. He continued representing British companies in Iran, as well as Iran Air in London, and elaborated support for Armenian causes in England and Armenia. Haig Galustian passed away in London on 9 December 1987.

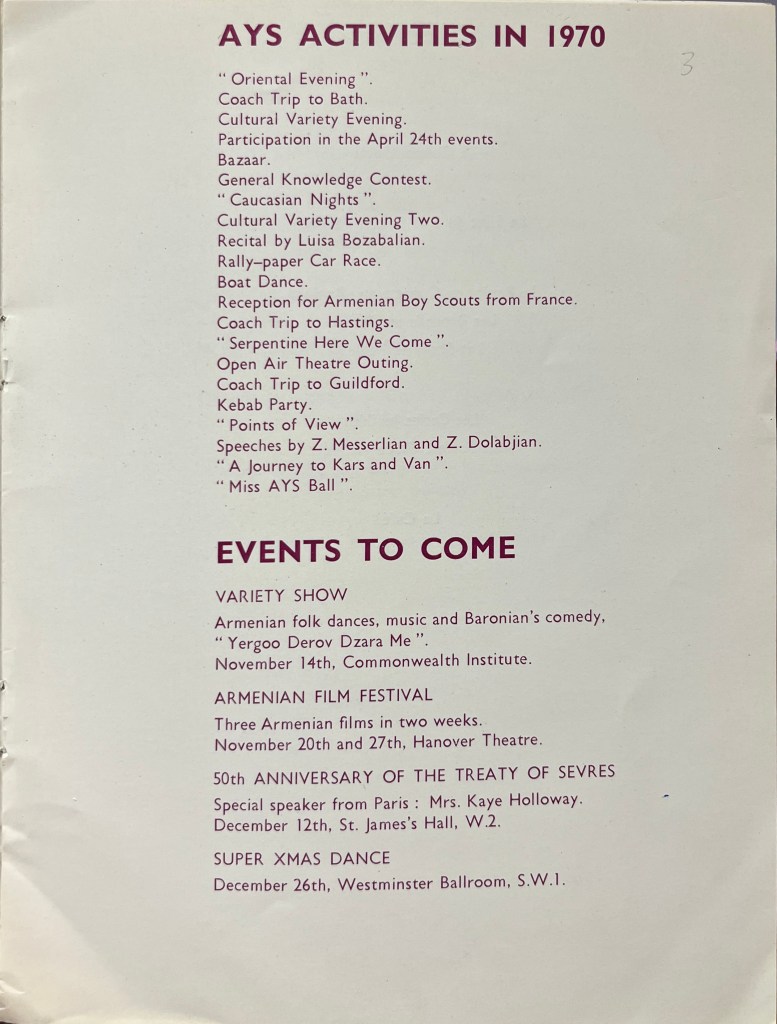

The organization of London communities and Armenian youth in particular was also the focus of two men connected to another item in the same case as Aregak. Tavit’ (David) and Haig Messerlian (Դաւիթ եւ Հայկ Մսըրլեան) were Lebanese-Armenians brothers active in London from the 1960s onwards. Their brother Dr. Zaven Messerlian, the Principal of the Armenian Evangelical College in Beirut, has been a great supporter of the British Library, donating copies of his own works on Armenian history as well as the archive of materials from which the Armenian Youth Society (AYS) membership card was drawn. In recent years, he has been a great source of assistance and inspiration as I catalogue the Daron Library acquired from the family of Ardashes Der-Khatchadourean.

Haig was the Chairman of the AYS during his time in London (1963-73), where he also led the Society’s folk dance troupe and edited its journal Sardabad. He then opted to migrate to the United States, where he was the Executive Director of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) from 1978 until 1987. A graduate of Central St. Martins School of Art (now located minutes from the Library), Haig was McCann Erickson’s Mexico Vice-President and Senior Creative Director until 2005. He still lives in Valencia-Santa Clarita, California, having built up an impressive and rich career in advertising. He has long been a supporter of Armenian causes, whether in his work with his numerous contributions to the memorialization of 20th-century diasporic Armenian life, or his lectureship at the American University of Armenia.

The final individual on our tour of personalities is someone who, very likely, needs no introduction. That’s because Ida Kar (her Wikipedia article; National Galleries of Scotland page), whose family’s last name was originally either Karamean (Քարամեան) or Karamanean (Քարամանեան), has had her own retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery in 2011 (check out the catalogue and the Guardian review by Sean O’Hagan). Born in Tambov, Russia in 1908, you’ll notice that her Armenian heritage is often added as a bit of trivia in some, but not all, of the descriptions of her life and work. And while it is, of course, standard practice to reference someone’s national origin based on the country in which they were born, it also obscures just how closely her biography maps many of the themes explored in Britanahay.

Tavit’, or David, who was born in Beirut in 1931, passed away in London 19 August 2007 at the age of 76. He emigrated to the UK in the 1960s after completing a degree in Commercial Studies at the University of Beirut. In England he was active in community organizations and commemorations. As we can see in the clipping of his obituary, Tavit’ was passionate about literature and the arts: he was the first Chairman of the Tekeyan Cultural Association (Թէքէեան Մշակոյթային Միւթիւն) in London as well as other bodies for the development of Armenian culture in the country. He was also politically active, a representative of the Armenian Democratic Liberal Party (Ռամկավար Ազատական Կուսակցութիւն; Ramgavar Party) in the UK. In 1979, Tavit’ gave an interview to the Lebanese Armenian daily Zart’ōnk’ (Զարթօնք; the scan of the original article from 25 September 1979) in which he detailed the evolution of Armenian communities in Britain, the migration of their centre from Manchester to London, and the revitalization of cultural and political life through social organizations. In her study of Armenian social networks in London, Armenians in London, Dr. Vered Amit remarks that she spoke with the Chairman of the Tekeyan Association in London in the 1980s without giving his name. At this point, Tavit’ would have been a Trustee of the Association, not its Chairman. She highlights the Assocation’s close connection to the Ramgavar Party and the intra-community political tensions arising from this. But she also emphasizes the Association’s active role in supporting the Armenian Scouts as well as a host of cultural activities for the community and for UK-Soviet Armenia relations.

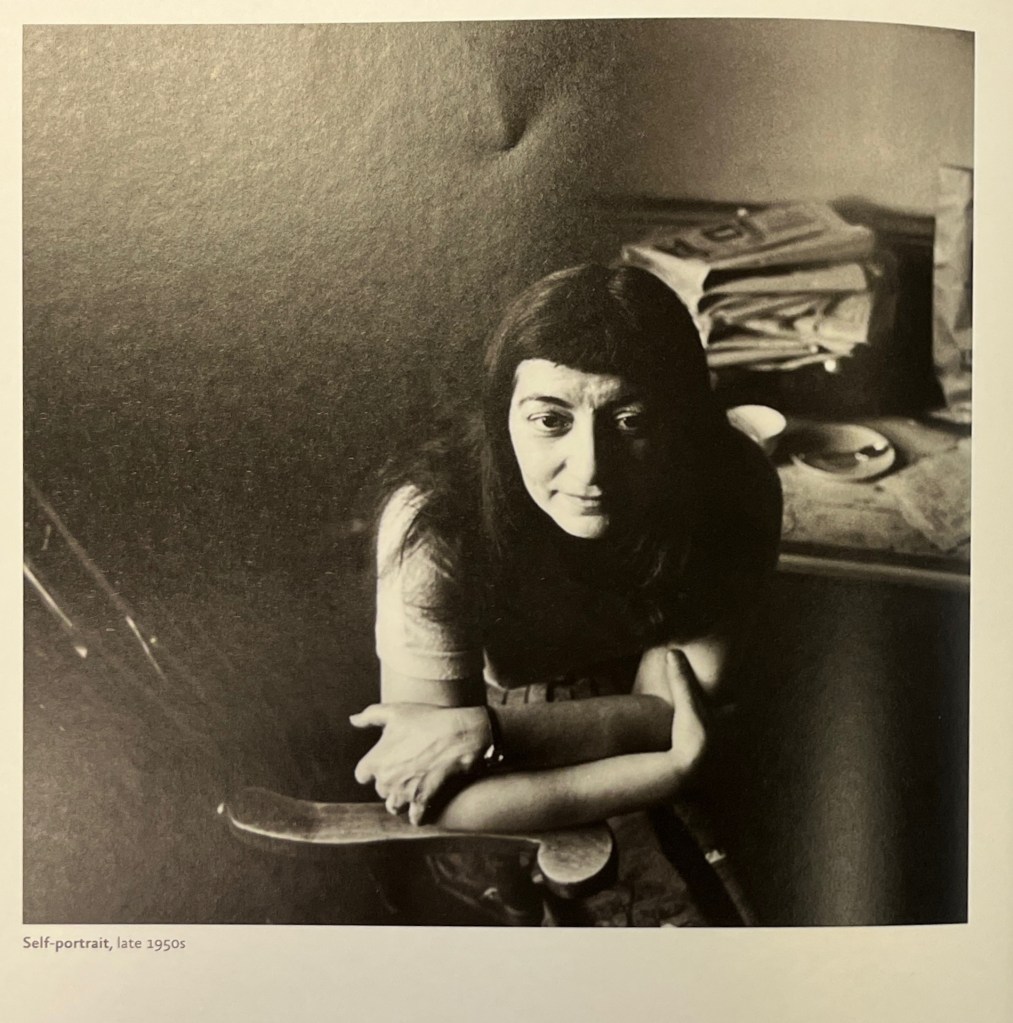

The final individual on our tour of personalities is someone who, very likely, needs no introduction. That’s because Ida Kar (her Wikipedia article; National Galleries of Scotland page), whose family’s last name was originally either Karamean (Քարամեան) or Karamanean (Քարամանեան), had her own retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery in 2011 (check out the catalogue and the Guardian review by Sean O’Hagan). Born in Tambov, Russia in 1908, you’ll notice that her Armenian heritage is often added as a bit of trivia in some, but not all, of the descriptions of her life and work. Indeed, it’s mentioned in passing in Surrealist Women: An International Anthology and not at all in Surrealism in Egypt: Modernism and the Art and Liberty Group. And while it is, of course, standard practice to reference someone’s national origin based on the country in which they were born, it also obscures just how closely her biography maps many of the themes explored in Britanahay.

As a child, Kar’s father moved the family from Russia to Iran shortly after the Russian Revolution and from there to Alexandria, Egypt, where Ida received a French-language education. She was soon immersed in the heady world of photography, surrealist art and creative pursuits in Egypt, with a five-year stint in Paris (1928-33) during which she took in the first showing of Un Chien Andalou. Back in Cairo, she contributed photographs to two exhibitions of surrealist works before leaving for England in 1945 with her second husband, Victor Musgreave. Kar rapidly established herself as a talented portrait photographer in London, photographing many of the capital’s most notable creatives and participants in contemporary art scenes. 1960, she was the first photographer to have a solo show at the Whitechapel Gallery in East London.

Many accounts of Kar’s work make much of her engagement with the British art world, but in 1957 she also re-acquainted herself with Caucasian Armenia during her first trip back in over 30 years. She spent several months photographing the country and even exhibiting some of her photographs in Yerevan (the NPG says this happened in 1957; Lusarvest claims it was in 1959). It was the photographs from this trip that found their way into “Return to Armenia”, the photo reportage published in the Tatler and Bystander on 8 October 1957 currently on display in Britanahay. It was a pivotal moment for her re-evaluation of her Armenian heritage. Such questions of Ida’s Armenian-ness and her approach to Armenian culture are truly excavated in the catalogue for the 2011 NPG show even if they aren’t usually front and centre elsewhere.

Perhaps Kar is just too important for too many cities. Most English pieces, especially those online, emphasize Kar’s pivotal role in portrait photography in the capital. The Egyptian online magazine al-Madīna (المدينة), which focuses on the creative history of Cairo, included her as one of the key figures of the city’s Surrealist movement. Nicole Rudnick, writing about the 2011 show for the Paris Review, highlighted her engagement with the French capital rather than Armenia or Egypt. Ani Margaryan’s Chinarmart blog, focused on Chinese-Armenian artistic connections, brings out her Armenian connection more prominently.

In this way, Ida Kar is perhaps the best person on which to end this exploration. Like so many of the other individuals highlighted in this blog and across the display, her life links Armenian experiences across many countries and communities while remaining truly unique. It’s a theme we hope to emphasize in Britanahay. As much as patterns might be tempting, each of the items on display speaks to singular aspects of Armenian-British experiences inside the UK and around the world. Even more than a celebration, the display is an invitation to come learn more about them.

Britanahay Բրիտանահայ: Armenian and British is open to the public in the British Library‘s Sir John S. Ritblatt Treasures Gallery seven days a week from 27 September 2025 until 22 February 2026. Entry is free of charge.

The display was organized with the participation of the Armenian Institute and the generous support of the Benlian Trust. I would like to thank Dr. Zaven Messerlian, Principal of the Armenian Evangelical College in Beirut, for his guidance and assistance in the authorship of this post.

Leave a comment