Last year, I had the pleasure of writing a piece for AJAM Media Collective about the ideologies and misconceptions of Latinization for the Turkic languages. Latinization has, of course, been proposed or applied to many other languages with mixed results. Some campaigns are controversial. Others should be, but, apparently, don’t gain enough traction to reach that threshold. While cataloguing an archive of Armenian newspapers, I stumbled across one such example: evidence of a late-19th century effort at introducing the use of a modified Latin script for Western Armenian.

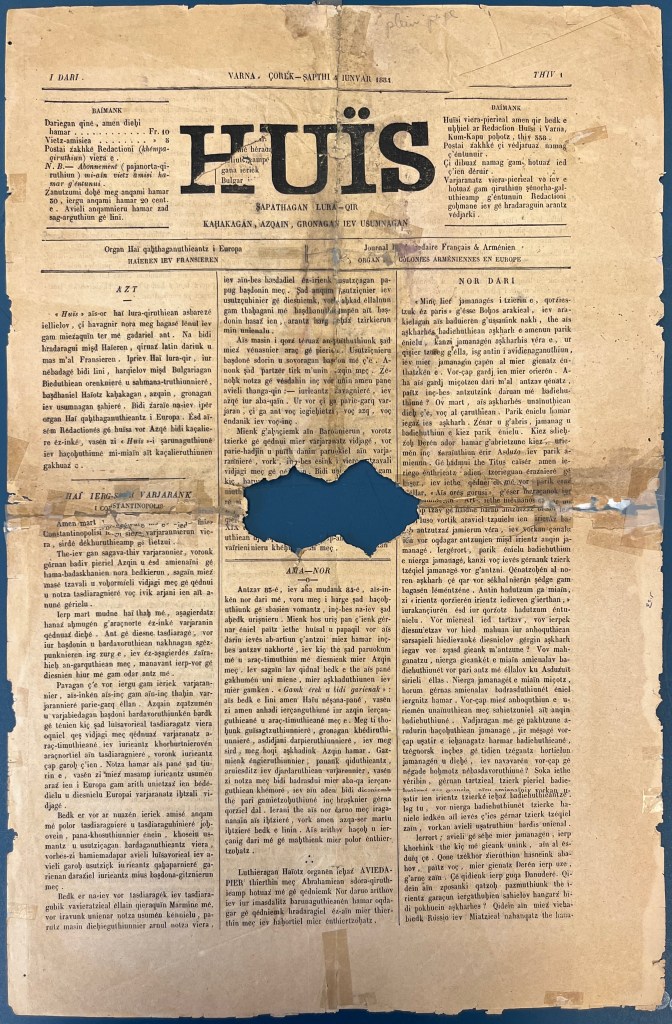

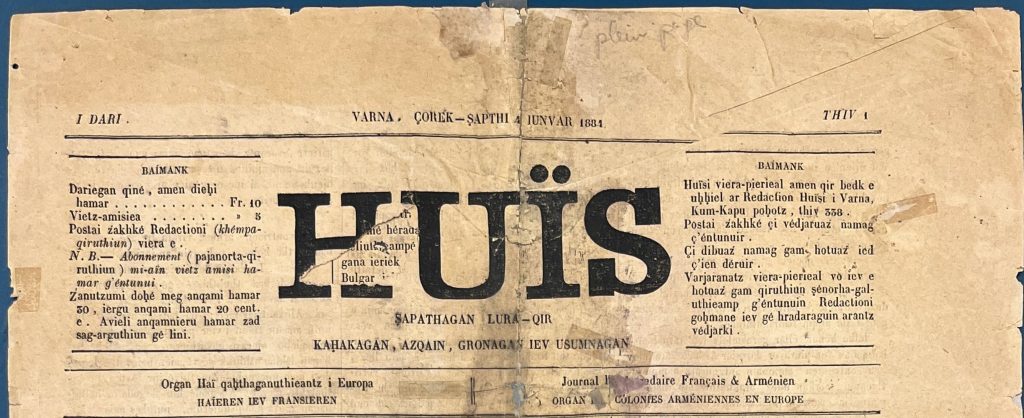

Huïs (Յոյս; Hope) was a weekly newspaper produced in Varna, Bulgaria starting on 4 January 1884. Managed by G. Gasparian and edited by A. I. Ioanessian, the periodical was written in Latin-script Western Armenian and French (which appeared towards the back) and was the self-described “organ of Armenian colonies in Europe” (Organ Haï qaḥthaganuthieantz i Europa; Օրկան Հայ գաղթականոութեանց ի Էւրոբա։). From the declensions of some of the words, it should be evident that the newspaper features grammatical elements common in late 19th-century Western Armenian texts that aren’t used in 20th century ones, like the -թեանց plural genitive ending. But even this very shaky student of Western Armenian can make out, with some ease, the meaning of the articles – once I get over the alienating features of the alphabet.

Let’s start with that. To make things easier for us all, here is a correspondence of signs found in Huïs and their Armenian equivalents:

| A | Ա | I | Ի | R | Ր, Ռ |

| B | Պ | Ï | Յ | S | Ս |

| Ç | Ջ, Չ | J | Ժ | Ş | Շ |

| D | Տ | K | Ք | T | Դ |

| E | Է | KH | Խ | TH | Թ |

| É | Ը | L | Լ | TS | Ձ |

| IE | Ե | M | Մ | TZ | Ց |

| F | Ֆ | N | Ն | U | ՈՒ |

| G | Կ | O | Ո, Օ | V | Վ, Ւ |

| H | Հ | P | Բ, Փ | Z | Զ |

| Ḥ | Ղ | Q | Գ | Ż | Ծ |

There are a few things to note. One is that the Latin alphabet has clearly been applied to reflect Western Armenian pronunciation but is not a complete phoneticization of the script. The letter d is used for տ, as one would expect in Western Armenian, and the two p’s, two r’s (were they distinct at this point?) and two ç’s have collapsed into one. But there are still some outliers, such as the split between t and th or between ts and tz, likely intended to reflect historic spelling rules and grammatical operations. IE is used wherever ե would be found, even when it’s pronounced like է or յ. And iu is used to reflect the sound իւ Beyond this, as you scan the columns of the newspaper, note that French understandings of orthography are at play: we never have gi, only gui, as if gi might be confused with j.

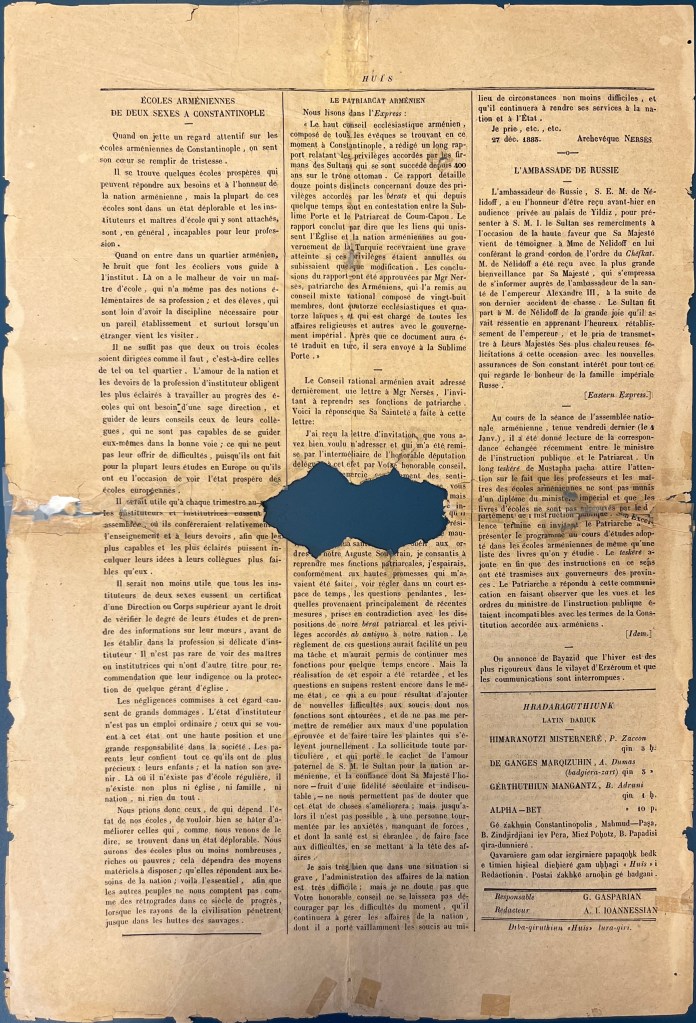

Now that we have matters of orthography out of the way, it’s time to turn to the content of the single issue on hand. Of the four (badly damaged) pages, two and a half are in Western Armenian and the final one and a half are in French. The French section contains both articles from other sources (Levant Herald and Eastern Express) including a report by Patriarch Nerses (Varjabedian) and an opinion piece about the importance of schooling for both boys and girls. The Armenian pages, in contrast, contain more original content, but are still heavily reliant on other publications. The first piece on page 1 informs us that the paper will promote Armenian political, national, religious and educational interests while remaining within the bounds of the Bulgarian government’s laws and the Bulgarian constitution. Nonetheless, Huïs has its eye on something big: to be the voice of Armenians in Europe.

Despite that European focus, much of the Armenian content for the newspaper seems to zero in on Istanbul. Whether the Editor’s opinion piece on the importance of teacher training, or the plethora of New Years greetings from Apostolic and Lutheran Church leaders, it is Bolis whose cultural, economic and political weight carries the day. This is an outsider’s view, evidenced by both the repeated assurances and effusive thanks offered to the Bulgarian government (quasi-independent since 1878), and the page-3 bits on constitutional development in the new Principality.

This external stance allowed Huïs to transliterate, effectively, snippets of news and development culled from Armenian-language publications coming out of the Empire as well as adjacent territories. Despite this ecumenical approach, the periodical was firmly within the late 19th-century social reformist trends of Ottoman Armenian intellectuals. Socio-economic and socio-political developments were both of great interest. Education was paramount: as the editor states, “Usutziçnieru bașdoné sdorin u sovoragan bașdon mé ç’e. Anonk șad partzér tirk m’unin azqin meç” (Ուսուցիչներու պաշտօնը ստորին ու սովորական պաշտօն մը չե։ Անոնք շատ բարձր դիրք մը ունին ազգին մէջ։ The teachers’ office is not a lowly and common office. They have a very high position in the nation). See also the piece from P’unj (Փունջ) about the poor quality of Armenian schooling in Romania and the spread of cholera in Alexandria. Or the considerable interest in exchanges between the Patriarch of Constantinople, Nerses II Varjabedian, and secular notables from the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian communities.

Huïs appeared at a crucial time in the history of Ottoman Armenians – just after the 1878 Congress of Berlin and transfer of Cyprus to Great Britain, and the British occupation of Egypt in 1882 – and the newspaper, despite its small size, did not miss out on being part of the fray. It is no wonder, then, that Latinization is taken in stride, clearly nothing more than a means to the end of national enlightenment and emancipation, conceived as being quasi-synonymous with Western Europeanization.

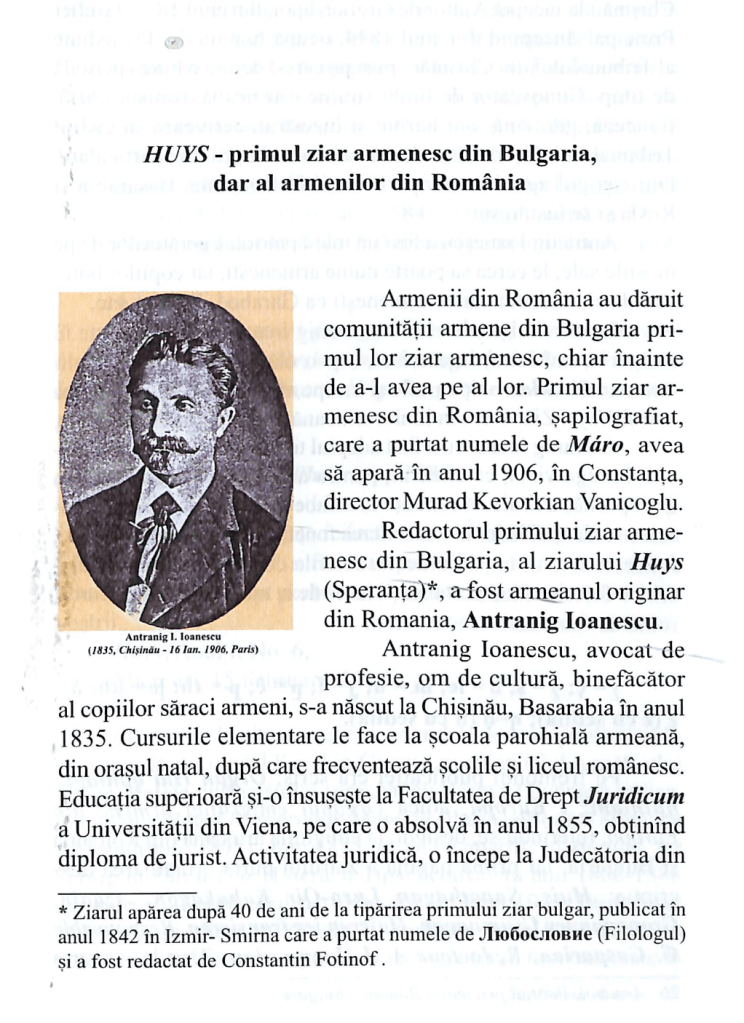

What, then, was the purpose of this broader foray into Armenian periodical publishing, and who dreamed it up? So far, I’ve only been able to find one article about the newspaper in the August 2014 supplement of Ararat: Periodic al Uniunii Armenilor din România (Ararat: The Periodical of the Union of Armenians in Romania). I don’t read Romanian, so I have been greatly assisted by Google Translate. Here we find that A. Ioanessian was Antranig I. Ionaescu, born in Chișinău, now Moldova, in 1835. After receiving Armenian parochial schooling and then education in Romanian institutions, he went to Vienna, where he received his Juris Doctor in 1855. He rose to the position of President of the Court of Chișinau in 1874. According to the article, he bought estates around Bessarabia, Romania and Russia, eventually moving to Varna, Bulgaria in 1883 and setting up a printing press in the Sisakian Armenian school, from which he began publishing Huïs in 1884.

Why did Ioanessian decide to publish in Latin characters? The piece in Ararat, which does not have an author listed, claims that Huïs was born from the editor’s firm belief that Armenians could only integrate into European society through the abandonment of Mesrop Mashtots’ alphabet and the adoption of the Latin one. Sound familiar? Of course, the Ararat piece also claims that he was influenced by the French, Romanian and Turkish alphabets, despite Huïs pre-dating the introduction of Latin script for Turkish by about 45 years.

Ioanessian gave up on his Latin-script project, but not on publishing. Indeed, between 1885 and his death in 1906, he worked tirelessly to publish a number of other patriotically-minded Armenian newspapers (always in Armenian script), as well as translations of French literature into Western Armenian. He was also a committed etymologist and amateur linguist with ideas that, well, don’t always accord with reality. He was especially keen on a project to compile a massive etymological dictionary that would show how every word in the world could be traced back to an Armenian root. Today, Ioanessian lies in the famed Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Sadly, his bright star means that he largely eclipsed his co-editor, Bolis-born Armenian mathematician and educator Bedros Adrouni, and the manager of Huïs, G. Gasparian.

It’s hard to tell how popular or wide-reaching the paper was, as only three copies of it exist in the Mekhitarist Congregation Library in Vienna. They hold copies of numbers 1, 6 and 37, which leads most scholars who have written about the newspapers to believe that it only lasted from 1884 until 1885 or 1886. A fourth copy, I have learned, can also be found at the National Library of Armenia, which has published online metadata for the newspaper and the images of issue 17 (31 October 1884). Here the editor is listed as Gasparian, but there is clearly little change in the format of the articles or the division of languages. The content is a bit more diverse than it was in issue 1, with a long piece by Ioanessian himself on Latin-Armenian etymological connections, and an unsigned piece about Mount Carmel. But most is sourced from elsewhere, especially the American Missionary magazine Avedaper (Աւետաբեր).

In the secondary literature, Huïs makes an appearance in a few publications about the Armenian press, including Nersēs Gasparean’s 1935 Ֆիլիպէ Հաե Լրագրութեան Ծագումը Պուլկարիոյ մէջ; in Teotig’s Ամէնուն Տարեցուցը (Բ Տարի, 1908); and in the Տիպ ու Տառ (1912). But the copy of Huïs from the British Library’s holdings is actually part of the Ardashes Der-Khachadourean archive that we took in in 1995. In this case, it might make most sense to have a look at what Der-Khachadourean wrote about Huïs for a few more clues.

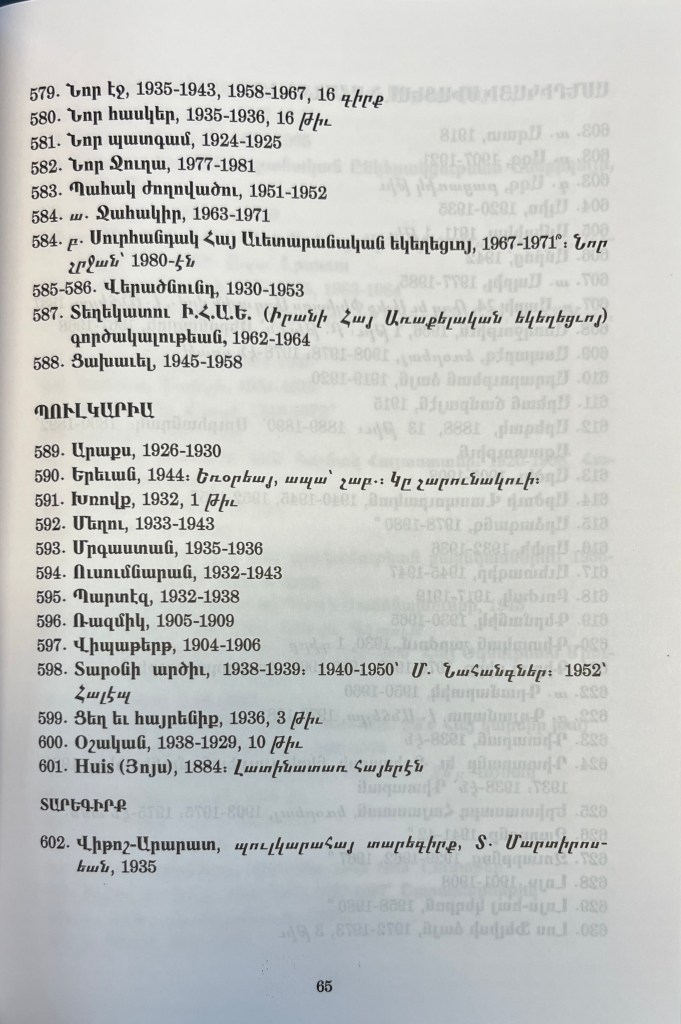

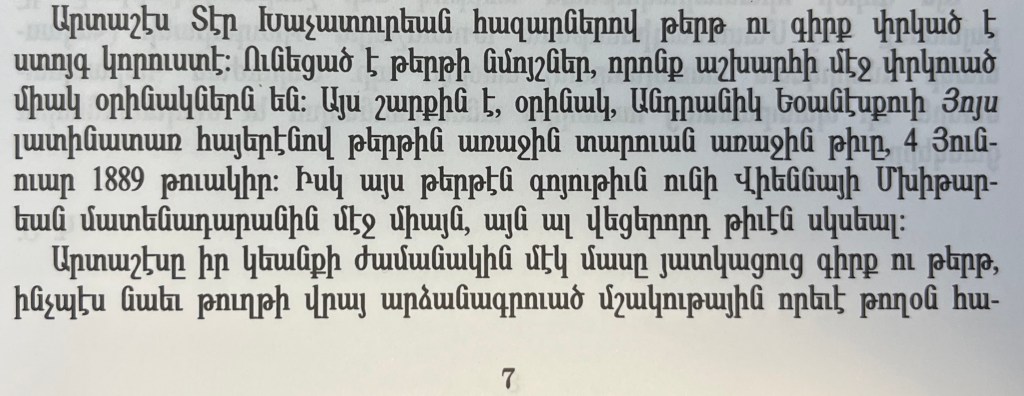

The answer is, not much. It should be no surprise that the title does appear in his Հայ Մամուլի Մատենագիտական Գործեր at number 601 – after all, I’m making use of the copy he acquired. But apart from the date of publication and the note that it is in Latin script (լատինաբառ), Der-Khachadourean provides us with precious little to go on. Indeed, I’m not able to find other entries in his catalogue under the name Ionessian. Ionescu (Եօանէսքու) does appear in the introduction to the volume, where G. Hovhannesian explains the uniqueness of Der-Khachadourean’s archive. A case in point is its incorporation of the first issue of Huïs, whose existence was attested only by a copy of the 6th issue in the Mekhitarist Library in Vienna.

In other words, we’re not much better off than we were from the newspaper alone. Ironically, what should have been a bit of a bang – the attempt to frame nearly 1500 years of Armenian writing as a hinderance to socio-political emancipation – was little more than a whimper. Huïs and Ioanessian’s broader efforts prove that writing systems are about so much more than just the logic and ease of the letters and orthography. They’re about state power, about political will, and, ultimately, about ideas sold to speakers through the medium of writing. Indeed, Huïs remains as a tribute to everyday Armenian readers’ capacity to resist stubbornly unwanted interventions.

Leave a comment